The keeping of reptiles in captivity is often undertaken with the aim of breeding the species in question. A fundamental prerequisite for successful breeding is knowledge of the sex of the animals.

Additionally, this information is necessary because same-sex individuals of many species can exhibit territorial behaviour, particularly upon reaching sexual maturity, which in the worst cases may result in aggressive encounters.

Although many reptiles, including numerous snake species, display clear sexual dimorphism, this is rarely apparent in juvenile animals, as it generally only develops over time. In many species, sexual dimorphism becomes fully expressed only upon reaching sexual maturity (Fig. 1). A prominent example is the anacondas (genus Eunectes), in which adult females grow many times larger than males. Another example is Wagler’s pit viper (Tropidolaemus wagleri), in which, in addition to sexual dimorphism, there is also sexual dichromatism—that is, a sex-specific difference in colouration and patterning.

While sex determination in adult individuals of many species is relatively straightforward, it becomes challenging in subadult or juvenile animals.

Correctly identifying the sex of hatchlings is particularly important, as these animals are typically transferred to new keepers at this early stage.

There are a number of manual methods for sex determination, each of which often has its own drawbacks.

1. Popping

The so-called “popping” technique involves manually everting the hemipenes of male snakes from the hemipenal pockets (Fig. 2). This method has the drawback that it is often applicable only to very young snakes, as the hemipenes of older individuals can no longer be everted. There is also a considerable risk of injury to the spinal region due to tail bending and the application of pressure immediately distal to the cloaca. Furthermore, there is always the risk of misidentification, as males may be incorrectly classified as females if eversion of the hemipenes is unsuccessful.

2. Probing

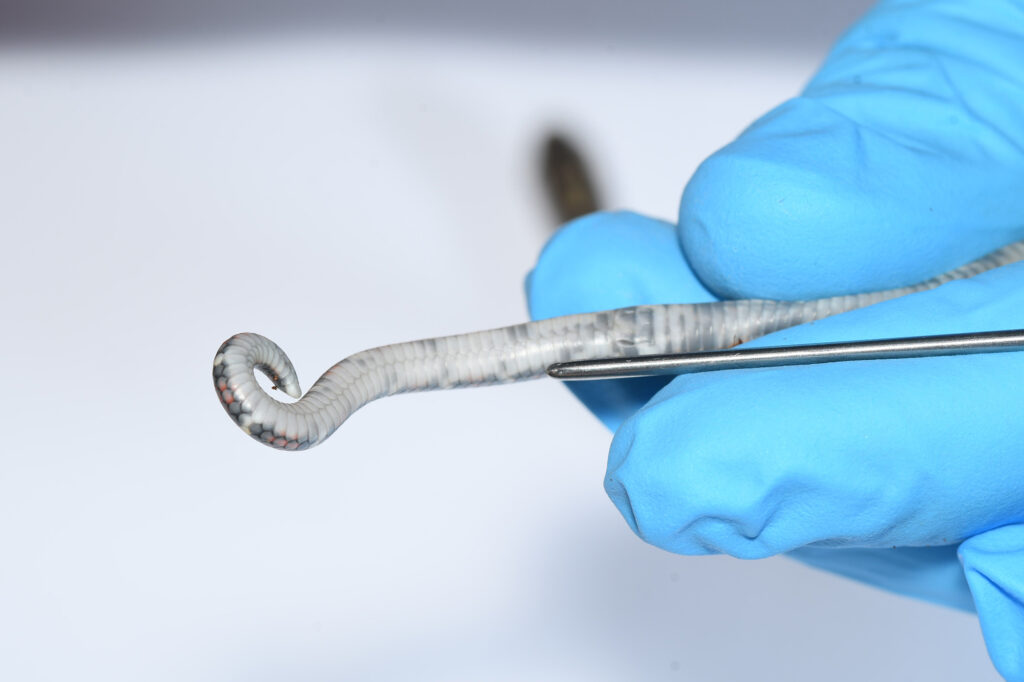

Probing involves inserting a metal probe into the hemipenes or hemiclitoral pockets just distal to the cloaca. The depth of insertion is measured by the number of subcaudal scales the probe passes. The deeper hemipenal pockets of male snakes allow for greater probe insertion. The main drawback is that probing very small snakes is simply not feasible due to the risk of injury, such as perforating the hemiclitoris of females (Fig. 3). There is also always a risk of misidentifi-cation, which can occur in either direction.

3. Visual Inspection

Certain characteristics can indicate a snake’s sex without further manipulation. These include, for example, tail shape or visible sexual traits, such as hemipenal pockets on the dorsal scales of colubrids (Fig. 4). However, these methods require considerable experience, are highly unreliable, and should be applied with great caution.

-

Fig. 1: Sexual dimorphism in the steppe rat snake (Elaphe dione), male above, female below

Image source: Gregor Geisler

-

Fig. 2: Everted hemipenis in a juvenile Archelaphe bella chapaensis

Image source: Gregor Geisler

-

Fig. 3: Hatchlings of many species should not be probed due to the high risk of injury

Image source: Gregor Geisler

-

Fig. 4: Hemipenal pockets can sometimes be observed on the dorsal scales of adult colubrids

Image source: Gregor Geisler

-

Fig. 5: In PCR, a gene segment on the W chromosome of females is amplified, which can subsequently be visualised on a gel

Image source: Gregor Geisler

Due to the numerous drawbacks of classical methods, we have established a molecular biological approach that allows reliable sex determination in many species. This method detects specific genes on the W chromosome of female snakes (Fig. 5). Suitable sample materials include shed skins, mucosal swabs, or EDTA blood. The advantages are clear: sex determination can be performed irrespective of age, and there is no risk of injury. Sample collection is very straightforward and therefore poses no difficulties for snake keepers.

We have already successfully applied our method to over 80 snake species and continue to expand our offerings. Genetic sex determination is currently available for vipers, pit vipers, and most colubrid species. All commonly kept species, such as corn snakes, king snakes, and hognose snakes, can be reliably sexed. For boas and pythons, we are currently developing a separate method, with the aim of providing a genetic sexing test for these groups in the future.

Conclusion

Sex determination in snakes, particularly in hatchlings, has long been a challenge. The genetic test now provides a safe and reliable alternative to traditional methods.

Gregor Geisler