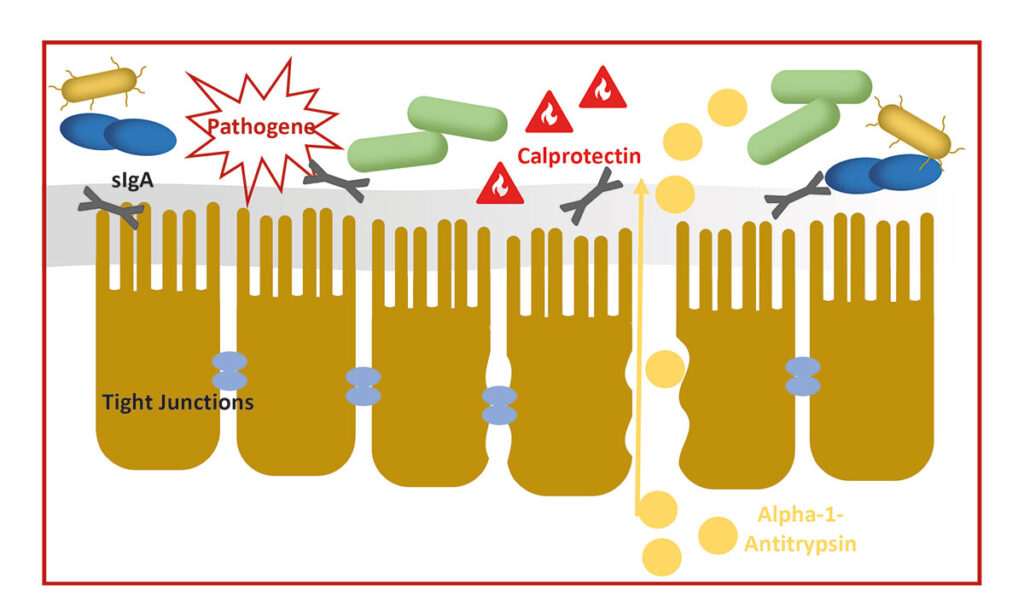

Faecal biomarkers represent a valuable, non-invasive tool for gaining insights into pathophysiological processes in the gastrointestinal tract. They enable the differentiation between inflammatory and non-inflammatory causes of chronic enteropathies, provide indications of protein loss, and assist in monitoring disease progression and guiding therapeutic decisions. Below, we present the most important faecal biomarkers currently available in veterinary medicine.

-

Faecal Biomarkers in Feline and Canine Chronic Enteropathies

Image source: Laboklin

1. α1-Antitrypsin

α1-Antitrypsin (α1-AT) is a protein belonging to the serine protease inhibitor (serpin) family. It is primarily synthesised in the liver and circulates in the blood plasma at relatively stable concentrations. Its physiological function is to inhibit proteolytic enzymes — particularly neutrophil elastase — in order to prevent tissue damage caused by excessive inflammatory responses. α1-AT is of particular diagnostic relevance in cases of protein-losing enteropathy (PLE). Unlike many other proteins, α1-AT is largely resistant to enzymatic degradation within the gastrointestinal tract. When intestinal barrier function is compromised — e.g. due to inflammation or ulceration — α1-AT may leak from the plasma into the intestinal lumen and can be detected intact in faeces. This makes α1-AT an ideal faecal marker for identifying plasma protein loss via the gastrointestinal tract. Detection in faeces indicates impaired intestinal barrier integrity and is considered a marker of intestinal protein loss.

Indication

In dogs, faecal α1-antitrypsin has been particularly well studied as an early marker for developing protein-losing enteropathy (PLE) in predisposed breeds (e.g. Soft Coated Wheaten Terrier). Studies indicate that the marker can detect intestinal barrier dysfunction at an early stage – before clinical signs or detectable hypoalbuminaemia in blood are present. Another potential application is in the evaluation of hypoproteinaemia or hypoalbuminaemia. Since PLE does not always present with diarrhoea, faecal α1-AT can be a useful tool to help identify the cause of such abnormalities in bloodwork. In patients with chronic enteropathy, increased faecal α1-AT concentrations are indicative of more severe intestinal disease. Additionally, the marker can be used for therapy monitoring: decreasing values during treatment suggest an improvement in intestinal barrier function.

Points to Consider

Measurement is typically performed via ELISA. Even small amounts of α1-antitrypsin escaping through a damaged mucosa can be detected. However, both diurnal variation and uneven distribution within a single faecal sample are known issues. This may result in low or undetectable concentrations being reported despite the presence of disease. Testing three consecutive faecal samples increases diagnostic accuracy.

Interpretation of faecal α1-AT concentrations should always be made in the clinical context. The reference interval is broad, and overlap with healthy control animals is possible. Diurnal fluctuations and uneven distribution in the faeces can lead to both false-positive and false-negative results. It is also important to consider that concentrations may be elevated in the presence of gastrointestinal bleeding or increased mucus production in the intestines.

α1-antitrypsin does not provide information on the aetiology of a PLE – it is a quantitative marker of protein loss, not specific for inflammation or neoplasia.

α1-Antitrypsin in Cats

Data are also available for cats, indicating that α1-antitrypsin concentrations can be significantly elevated in cases of chronic enteropathy. As with dogs, interpretation should always be made in the clinical context. Overall, chronic enteropathy in cats appears to be more frequently associated with intestinal protein loss than in dogs. As a result, defining a protein-losing enteropathy (PLE) in this species is more challenging.

2. Calprotectin

Calprotectin is a calcium-binding protein from the S100 protein family, primarily found in neutrophilic granulocytes. It is released in increased amounts during inflammatory processes. In cases of gastrointestinal inflammation, calprotectin is secreted across the intestinal mucosa into the lumen and can therefore be detected in faeces.

Its measurement in faecal samples allows for a non- invasive assessment of inflammatory activity in the gastrointestinal tract – a method that is well established in human medicine and increasingly applied in veterinary medicine.

Indication

In dogs, faecal calprotectin is used as a marker for chronic inflammatory bowel disease. Studies have shown that elevated concentrations correlate with both the severity of histological changes and the clinical activity index (CCECAI). It can be helpful for differentiating between inflammatory and non-inflammatory diarrhoea, assessing disease activity, and monitoring treatment response.

The significance of calprotectin lies particularly in its ability to reflect the severity of chronic enteropathy. Studies have demonstrated that dogs with a higher CCECAI (e.g. ≥12) exhibit significantly increased values. The parameter can provide insights into the need for immunosuppressive therapy and support prognostic evaluations. The higher the faecal calprotectin concentration, the more likely it is that the patient will require immunosuppressive treatment. In follow-up assessments, a failure of levels to normalise may indicate incomplete remission. A renewed increase can occur even before clinical deterioration becomes apparent.

Points to Consider

As with all biomarkers, calprotectin is not disease- specific. It merely indicates the presence and extent of inflammation. Elevated levels may also be observed in bacterial infections, parasitic infestations, or neoplastic diseases. Interpretation should therefore always occur within the clinical context and be supported by further diagnostic investigations (e.g. imaging, endoscopy, histology). Faecal calprotectin concentrations within the reference range do not exclude the presence of enteropathy. This is particularly relevant in dogs, where the predominant inflammatory response tends to be lymphoplasmacytic rather than neutrophilic. Additionally, many enteropathies in dogs appear to be food-responsive, and in such cases, a strong neutrophilic inflammatory response – and therefore elevated calprotectin levels – is not expected.

Calprotectin in Cats

Calprotectin has also shown promising results in cats. It is used as a supportive marker in cases of chronic diarrhoea. Particularly relevant are investigations into its potential for differentiating between inflammatory and neoplastic processes (e.g. low-grade lymphoma). Faecal calprotectin concentrations may be significantly higher in cases of lymphoma; however, a reliable differentiation has not yet been clearly demonstrated.

3. Zonulin

Zonulin is an endogenous protein that plays a central role in regulating intestinal permeability. It controls the permeability of the tight junctions – those cellular connections that link intestinal epithelial cells and thus prevent the intrusion of unwanted substances. Increased zonulin release leads to the loosening of these junctions, resulting in increased intestinal permeability – a condition commonly referred to as “leaky gut”.

Under physiological conditions, zonulin allows a temporary opening of the intestinal barrier, e.g. for immune surveillance or transport processes. This regulation is finely tuned and normally reversible. Pathological conditions arise when this opening is prolonged or excessive, permitting the passage of bacterial components, toxins, or incompletely digested dietary proteins into the tissue.

Indication

Zonulin has been identified as a potential marker for the integrity of the intestinal barrier. Elevated faecal or serological zonulin levels have been described particularly in dogs with chronic enteropathy, food allergies, or inflammatory bowel disease. Studies indicate that dysregulated zonulin expression is associated with increased intestinal permeability, i.e. a disturbed barrier mechanism. The determination of zonulin therefore offers a non-invasive insight into the functionality of the intestinal mucosa. Despite the currently limited amount of clinical data available for small animals, the measurement of zonulin opens up new diagnostic and therapeutic perspectives for a holistic approach to gastrointestinal diseases.

What should be considered

Zonulin is not a disease-specific marker.

As with many newer biomarkers, results must be interpreted in the overall clinical context.

Elevated values alone do not allow a diagnosis but can provide indications of functional disturbances of the barrier. Factors such as stress, medication, age, or diet may influence its concentration.

Zonulin in cats

Initial pilot studies in cats suggest that the protein may also play a role in feline chronic enteropathies (e.g. lymphoplasmacytic enteritis or low-grade lymphomas).

4. Faecal secretory immunoglobulin A (sIgA)

Immunoglobulin A (IgA) is a central component of mucosal immune defence. It is produced as secretory IgA (sIgA) by plasma cells in the lamina propria of the intestine and actively transported across the epithelium into the intestinal lumen. There, it forms a first line of defence against pathogenic microorganisms without triggering inflammatory responses. sIgA thus acts as a ‘bouncer’, protecting the mucosa from bacterial adherence, toxin activity, and invasion. Secretory IgA binds to surface antigens of bacteria, viruses, or toxins and neutralises them before they come into contact with epithelial cells. Unlike IgG or IgM, IgA does not activate the complement system and is therefore non-inflammatory. This is essential for immunological tolerance in the intestine, where numerous harmless antigens (e.g. food components, commensals) are constantly present.

Indication

A reduced concentration in faeces may indicate a functional immunodeficiency of the intestinal mucosa. Reduced sIgA production has been particularly described in German Shepherds with chronic enteropathy.

What should be considered

sIgA is regarded as an indicator of mucosal immunocompetence in the intestine, although interpretation must be approached with caution, as it can be influenced by age, stress, diet, and even sample handling. Measurement should be performed on the freshest faecal samples possible.

sIgA in cats

Data on faecal sIgA in cats are still limited. However, initial studies suggest that reduced sIgA concentrations in faeces can occur in chronic intestinal diseases, such as inflammatory enteritis or intestinal lymphoma.

5. Canine pancreatic elastase 1

Elastase is a proteolytic enzyme produced in the exocrine pancreas and released into the small intestine with pancreatic juice. Its main function is to break down elastin, a structural protein in connective tissue. In diagnostics, however, its enzymatic activity is of less importance than the detection of stable amounts of elastase in faeces, which allows conclusions to be drawn about exocrine pancreatic function. In contrast to many other pancreatic enzymes, elastase in the intestinal lumen is largely resistant to enzymatic degradation, bile acids, and bacterial influences. It is excreted unchanged in faeces and can be detected using immunological tests (ELISA), making it a non-invasive marker of exocrine pancreatic function. In dogs, measurement of pancreatic elastase 1 is a useful screening tool, particularly in patients with non-specific gastrointestinal signs. It can serve as a supplement or preliminary test to determine specific trypsin-like immunoreactivity (cTLI). Normal elastase values generally rule out clinically relevant exocrine pancreatic insufficiency (EPI). Significantly reduced values may indicate exocrine dysfunction, but confirmation with serum cTLI is required.

Low faecal elastase concentrations can occur, for example, due to the dilution effect in diarrhoea and are therefore not conclusive for EPI on their own.

Low concentrations can also be observed in healthy dogs. A cTLI concentration within the reference range argues against the presence of EPI, even if faecal elastase is very low. Only in very rare cases is EPI accompanied by low faecal elastase but normal or low-normal cTLI concentrations.

This can occur in situations such as occlusion of the pancreatic duct (the pancreas itself remains functional, but the enzymes do not reach the intestine), or when blood sampling for cTLI is not performed under fasting conditions or occurs during an episode of pancreatitis (residual enzyme still present is released into the blood).

6. (Total) bile acids

Bile acids are synthesised in the liver and secreted into the small intestine during digestion.

Approximately 95% are reabsorbed in the ileum. Disruption of this reabsorption – for example, due to chronic inflammation – leads to increased amounts of primary bile acids in the colon, which can trigger secretory diarrhoea. Similarly, dysbiosis with reduced conversion into secondary bile acids by Clostridium hiranonis (renamed Peptacetobacter hiranonis) can affect these processes.

7. Dysbiosis investigations

The intestinal microbiota plays a key role in the pathogenesis of chronic enteropathies. Dysbiosis tests quantify relevant bacterial marker species (e.g. Faecalibacterium, Turicibacter, Clostridium hiranonis) using PCR-based methods and assess their deviation from the physiological state. An altered score indicates disrupted microbial homeostasis and may have prognostic relevance.

Conclusion

Over recent years, the evaluation of faecal biomarkers has become increasingly integrated into the diagnosis and therapeutic monitoring of chronic enteropathies. While α1-antitrypsin and calprotectin can provide direct indications of protein loss and inflammation,other may offer additional information on the functional and microbial integrity of the gut. Their targeted use can provide a basis for therapeutic decisions, follow-up assessments, and prognosis. It remains essential to interpret results in the clinical context and, where appropriate, to combine several parameters to enhance diagnostic value.

Dr. Jennifer von Luckner

Our services for enteropathies

- Intestinal profile (serum)

- Diarrhoea profiles (faeces)

- Parasite profiles (faeces)

- Dysbiosis analysis (faeces)

- Dysbiosis profile (faeces)

…and many more.