Canine and feline intraocular neoplasia are relatively rare, when compared to neoplasia affecting other organs. Primary tumours are more common than metastatic disease.

The clinical diagnosis of intraocular tumours is often challenging. In contrast to tumours in the skin, neoplasia in the eye may not be readily visible and remain unapparent from the external surface of the eye. Intraocular tumours can also cause variable clinical symptoms, depending on the exact intraocular structures involved or affected by the mass, further complicating the clinical diagnosis.

As a consequence, even very small and/or benign tumours can have dramatic effects on the ocular function. Loss or impairment of vision, tissue destruction and secondary glaucoma are common clinical symptoms leading owners to opt for a veterinary consult. Although the impact varies depending on the anatomical location of the neoplasm, ocular neoplasia is a common reason for enucleation.

In both dogs and cats, reviews in literature identify melanocytic tumours as the most common primary intraocular neoplasm. According to the WHO classification, melanocytic tumours are divided into two groups: benign tumours referred to as melanocytoma, and malignant tumours referred to as melanoma.

In the eye, the anterior uvea is considered as most common intraocular location for development of melanocytic tumours in animals. In dogs, tumours are most often benign, but in cats, tumours are most often malignant. In contrast, melanocytic neoplasia in the posterior uvea is rare in both canine and feline species, and most tumours are benign in this location.

The unique features of the two most frequently recognized entities in dogs and cats will be discussed in more detail below.

Feline diffuse iris melanoma (FDIM)

Melanocytic tumours account for 67% of all feline primary ocular neoplasia. Feline diffuse iris melanoma is by far the most common ocular melanocytic neoplasm in cats, with limbal and atypical melanomas being uncommon melanocytic tumour variants far less often diagnosed.

Feline diffuse iris melanoma can occur in cats of any age, with an average age of 9.4 years. A breed or sex predilection has not been reported.

Feline diffuse iris melanoma is a malignant disease, with a highly variable clinical appearance, making diagnosis sometimes challenging, especially in early stages of the disease. Lesions often start as one or multiple small pigmented foci on the iris, macroscopically visible as flat black spots. These spots are referred to as iris melanosis, and are considered a benign precursor stage of feline diffuse iris melanoma.

The progression of the disease is highly variable and therefore unpredictable. Lesions may remain stable for months or even years, while some foci show very rapid progression with locally invasive growth and metastatic disease in a short time period.

This complicates clinical management as well.

Clinically, iris melanosis and early stages of feline diffuse iris melanoma are indistinguishable.

The transition from iris melanosis to malignant feline diffuse iris melanoma can only be confirmed by histological examination. In iris melanosis, melanocytes are solely confined to the superficial layers of the iridial surface. As soon as atypical melanocytes are expanding into the iridial stroma, lesions are progressed to feline diffuse iris melanoma.

In this stage, iris thickening, pupil shape changes (dyscoria) and reduced mobility of the pupil can be observed clinically.

-

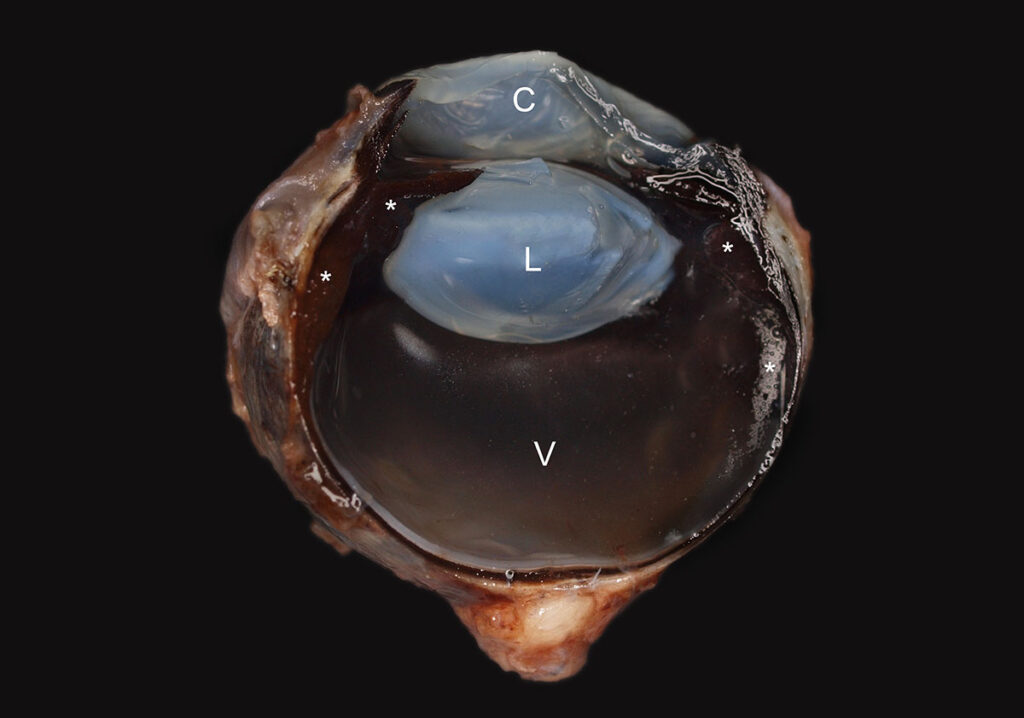

Fig. 1: Macroscopical view of a canine anterior uveal melanocy- toma (*) affecting the uvea, transverse section. C = cornea, L = lense, V = Vitreous.

Image source: Laboklin

-

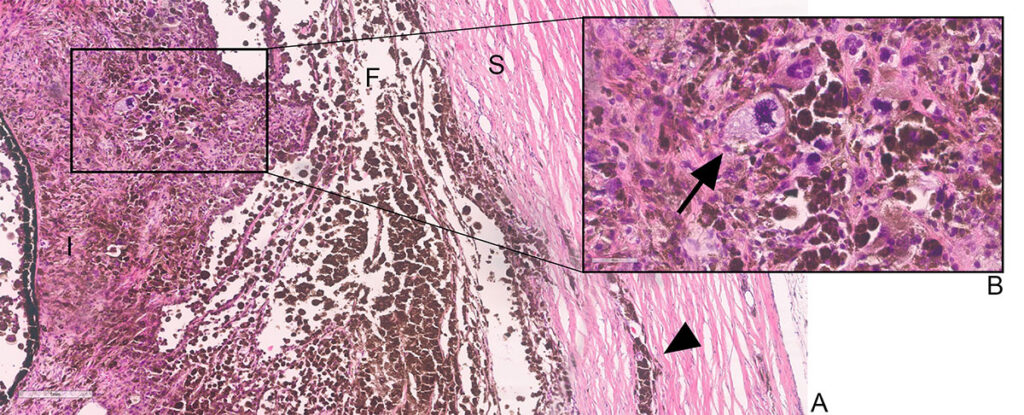

Fig. 2 A: Feline diffuse iris melanoma, filtration angle (F) region. The iris (I) is expanded by numerous poorly differentiated, moderately pigmented melanocytic tumour cells. Invasive growth (arrowhead) into the adjacent sclera (S) is visible.

HE staining, 8x magnification. Scale bar: 1mm. B: Inset, arrow: atypical mitotic figure. Surrounding cells show moderate cellular and nuclear atypia. HE staining, 20x magnification. Scale bar: 80μm.

Image source: Laboklin

-

Fig. 3 A: Eye, overview. Canine anterior uveal melanocytoma affecting the normal iris structure (square) with mild infiltrative growth (ellipse) in the adjacent sclera. L = lens, C = cornea, R = retina. HE staining, 0.6x magnification. Scale bar 4mm. B: Detail of the mass. Well-differentiated neoplastic melanocytes, highly pigmented, polygonal in shape. HE staining, 40x magnification. Scale bar: 60μm.

Image source: Laboklin

Progression of the disease can either be slow or rapid.

Unfortunately, there is no reliable method available to predict the speed of progression up to now, as factors influencing the speed of progression remain unknown. In case of slow progression, early signs include an increase in the number or size of the black spots in the iris. The iris surface can become irregular, rather than smooth.

As progression continues, locally invasive growth can be seen in the surrounding tissues (Fig. 2A+2B).

The masses can expand into the iris, iridocorneal angle and ciliary body to varying degrees, and sometimes affect the whole globe and surrounding tissues. In cases where the filtration angle gets obstructed, the drainage of aqueous humour is blocked and secondary glaucoma develops.

In advanced cases, metastatic disease may occur. Whereas intraocular metastasis likely occurs via exfoliation of tumour cells into the aqueous humour, haematogenous spread through the scleral venous plexus is the most likely route for extraocular metastases, making invasion of the scleral venous plexus an important prognostic factor.

Metastases are most commonly reported in abdominal organs, especially the liver.

Spleen, lymph nodes, bone and lungs can be involved as well.

Unfortunately, data on the metastatic potential are sparse. Reported metastatic disease rates vary from 19-63%. However, these studies are often based on low case numbers, or include relatively high numbers of already advanced cases.

As a consequence, these results need to be interpreted carefully as they may lead to a false overestimation of the incidence of metastatic disease. Although the period between the diagnosis of FDIM and death from metastatic disease can involve multiple years, the prognosis therefore remains guarded.

To date, the only treatment option available for feline diffuse iris melanoma is enucleation.

Adjuvant therapies for metastatic disease of feline diffuse iris melanoma, as used for canine melanoma, are not available. A diagnosis of iris melanosis should be interpreted with caution, as lesions can progress quite fast and become malignant. Careful and frequent clinical re-examination is therefore recommended.

Negative prognostic indicators for meta- static disease in FDIM:

- Mitotic count of > 7 per high power field

- Invasion of the scleral venous plexus, choroid and extrascleral connective tissue

- Tumour necrosis

- Secondary glaucoma

Canine anterior uveal melanocytic tumours

Canine anterior uveal melanocytic tumours are the most common primary intraocular tumours in dogs. Tumours are most often seen in middle-aged to older dogs, but can occur at any age. A breed or sex predilection is not known. In general, and in contrast to feline diffuse iris melanoma, canine uveal melanocytic tumours are generally considered benign.

Colloquially, canine anterior uveal melanocytic tumours are often referred to as melanomas, despite their generally benign biological behaviour. According to the WHO classification, however, the benign variants should correctly be called melanocytoma, and the malignant melanoma.

Clinically, canine uveal melanocytic tumours have a variable appearance and often affect the iris, ciliary body, or both. Rarely, the choroid is involved.

Local extension often leads to glaucoma, similar to the feline variant.

The benign canine anterior uveal melanocytoma has a rather uniform appearance, independent of the exact intraocular site where they develop.

Usually, these tumours are heavily pigmented and composed of spindle-shaped to plump polygonal cells showing only minimal cellular and nuclear atypia (Fig. 3B). Mitoses are rare to absent.

Many canine uveal melanocytomas extend along the corneoscleral network into the adjacent corneal stroma. Additionally, the sclera and extrascleral tissues are often invaded by these tumours (Fig 3A)

Thus, even though benign, canine anterior uveal melanocytomas regularly show local invasive growth, which in other tumours often is interpreted as a sign of malignancy. However, metastatic disease is only reported in a minority of cases in canine anterior uveal melanocytic tumours, making locally invasive growth an unreliable parameter for malignancy and differentiation between benign and malignant variants.

In contrast, the mitotic count is a more important prognostic factor of malignancy, as metastatic disease is particularly observed in cases with a high mitotic count (> 4 per 10 high power fields).

Unfortunately, despite the mitotic count, other histological features predictive of malignant biological behaviour, remain unknown up to now.

In general, in the rare malignant variants (melanoma), cellular and nuclear atypia are prominent and tumours are often subtly or nonpigmented, making the diagnosis more challenging.

Immunohistochemical examination can be a valuable tool in these cases, to confirm the melanocytic origin of tumours cells.

Tab. 1: Overview of clinical characteristics of feline diffuse iris melanoma and canine anterior uveal melanocytoma

| Feline diffuse iris melanoma | Canine anterior uveal melanocytoma | |

| Nature | malignant | benign (majority) |

| Locally invasive growth | Yes, sign of malignancy | Yes, but not a reliable indicator of malignancy |

| Metastatic disease | Yes | No |

| Progression of disease | Highly variable | Slow |

| Prognosis | Guarded | Good after enucleation |

Conclusion

In general, in both canine and feline cases of uveal melanocytic tumours, it is difficult to differentiate between benign/precursor stages and malignant uveal neoplasia based solely on clinical appearance.

Cats presenting with hyperpigmentation in the iris should undergo a thorough physical and ocular examination. Histology is necessary in order to differentiate between iris melanosis and early stages of feline diffuse iris melanoma. Advanced imaging, including ultrasound, CT or MRI can be considered to evaluate the degree of invasive growth and presence of metastatic disease, as the metastatic potential in feline diffuse iris melanoma is higher than in canine anterior uveal melanocytoma.

Dogs with canine anterior uveal melanocytic tumours carry a good prognosis for life expectancy in the benign cases (melanocytoma), although enucleation is often recommended. In a minority of cases, tumours show a mitotic count of more than 4 per 10 high power fields, which are then classified as melanomas. Melanomas carry a guarded prognosis for life as malignant behaviour, faster progression and metastatic disease is more likely.

Further research is necessary in order to understand factors and mechanisms that influence the progression of feline diffuse iris melanoma and to more accurately predict metastatic disease in canine anterior uveal melanocytic tumours.

Our range of services for neoplasia:

- Pathohistology

- Pathohistology with increased complexity

- Cytology

- Immunohistological examinations

- and many more

Cynthia de Vries, DVM, Dipl. ECVP & Dr. Christina Stadler,

Specialist Veterinarian for Pathology