Transitional cell and prostate carcinoma

In dogs, both transitional cell carcinoma (TCC, Fig. 1) and prostate carcinoma (PCa) are highly malignant neoplasms (GRIFFIN et al. 2018). Both types of tumour are often diagnosed rather late (BRYAN et al. 2007; PANTKE 2018). Consequently, prognosis for affected dogs is bad (CORNELL et al. 2000; HENRY 2003). The median survival time is one year for dogs with TCC and 30 days for dogs with PCa (HENRY 2003; CORNELL et al. 2000). The median age of affected dogs is 11 (TCC) and 10 years (PCa) (CORNELL et al. 2000; KNAPP et al. 2000). For a long time, there was no reliable screening test for the presence of TCC, particularly for breeds with increased genetic risk (certain terrier breeds).

BRAF mutation

The presence of BRAF variant V595E, known from human medicine, was studied for the first time on a large number of tumours in dogs by MOCHIZUKI et al. in 2015. In contrast to people, where the mutation occurs mainly in malignant melanoma, ovarian tumours and colorectal carcinoma, in dogs, MOCHIZUKI et al. (2015) most often found the mutation in transitional cell and prostate carcinomas. It is a somatic mutation in the BRAF gene which only occurs in the tumour cells. It is assumed that this mutation leads to tumour development through permanent activation of the MAP kinase pathway.

BRAF mutation in canine transitional cell carcinoma

In 2018, we succeeded in establishing the method for detecting BRAF mutation in TCC in our laboratory (AUPPERLE-LELLBACH et al. 2018). Specificity was 100% as the BRAF mutation could not be detected in any of the dogs with cystitis, urinary bladder polyp or in those without any clinical and pathological signs. Sensitivity of BRAF mutation detection in TCC was 71%.

Possible sample materials:

- tissue (e.g. biopsies)

- cytological smears (e.g. FNA)

- urine rich in cells (early morning urine)

In the literature, the test has so far only been described for tissue samples and urine. In our studies, we have also succeeded in establishing it for cytological smears of fine needle aspirates and urinary sediments.

Thus, invasive sampling can be avoided by testing spontaneous urine, or there is no repeated invasive sampling necessary in cases of questionable histopathological and cytological diagnoses (poor sample quality, overlapping images of inflammation and neoplasia).

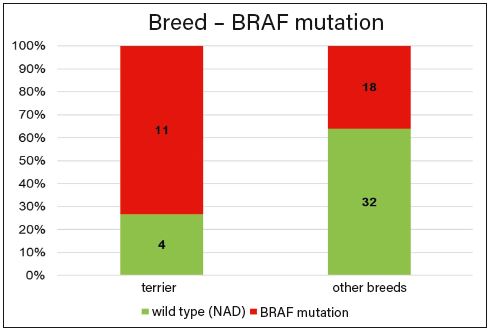

A breed predisposition has been described for canine TCC in Scottish, Fox and West Highland White Terrier (FULKERSON und KNAPP 2015). Another study also showed a predisposition for BRAF mutation in different long- and short-legged terriers (AUPPERLE-LELLBACH et al. 2019). It can thus be concluded that detection of BRAF mutation in these terrier breeds is not only highly specific for the presence of TCC, but also very sensitive (Fig. 2) and can be used as a screening test for the presence of TCC.

-

Fig. 1: Sonographic image of the urinary bladder. A papillary mass clearly protrudes into the lumen of the bladder.

©Tierklinik Rupphübel

- Fig. 2: Correlation between BRAF mutation and dog breed. Terriers were significantly more likely to show BRAF mutation in transitional cell carcinoma than other breeds.

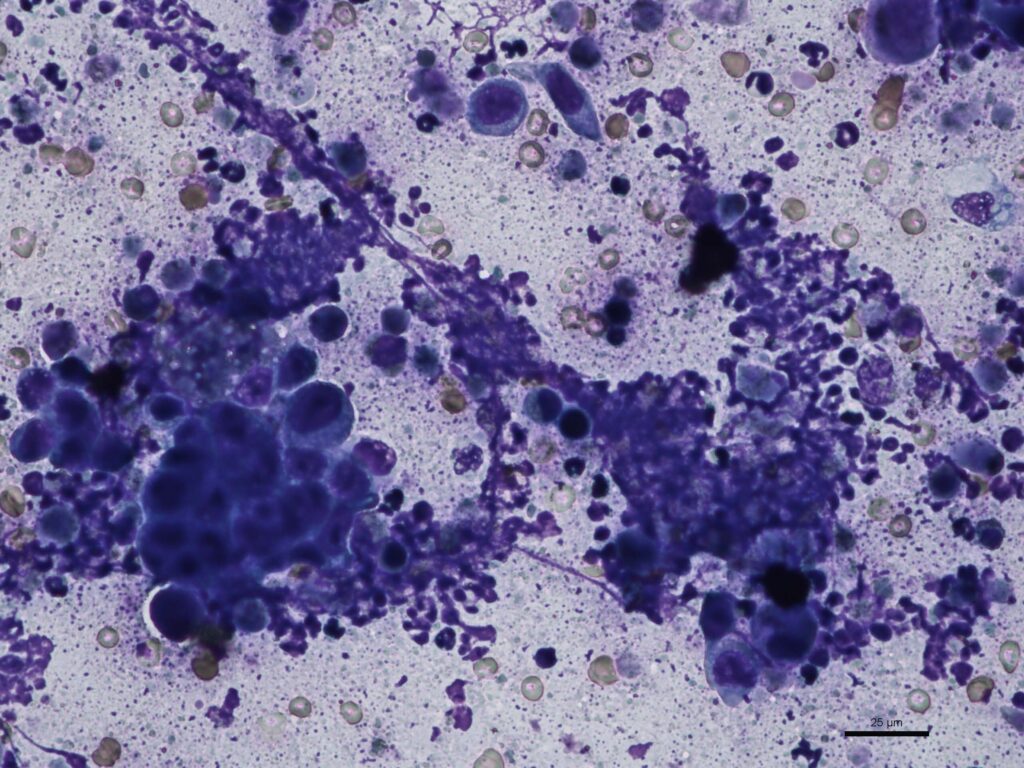

- Fig. 3: Cytological picture of prostate carcinoma with prostatitis: numerous partly degenerated neutrophil granulocytes and clusters of pleomorphic prostate epithelial cells with large, differently shaped cell nuclei (Haema Quick Stain, bar = 25 µm)

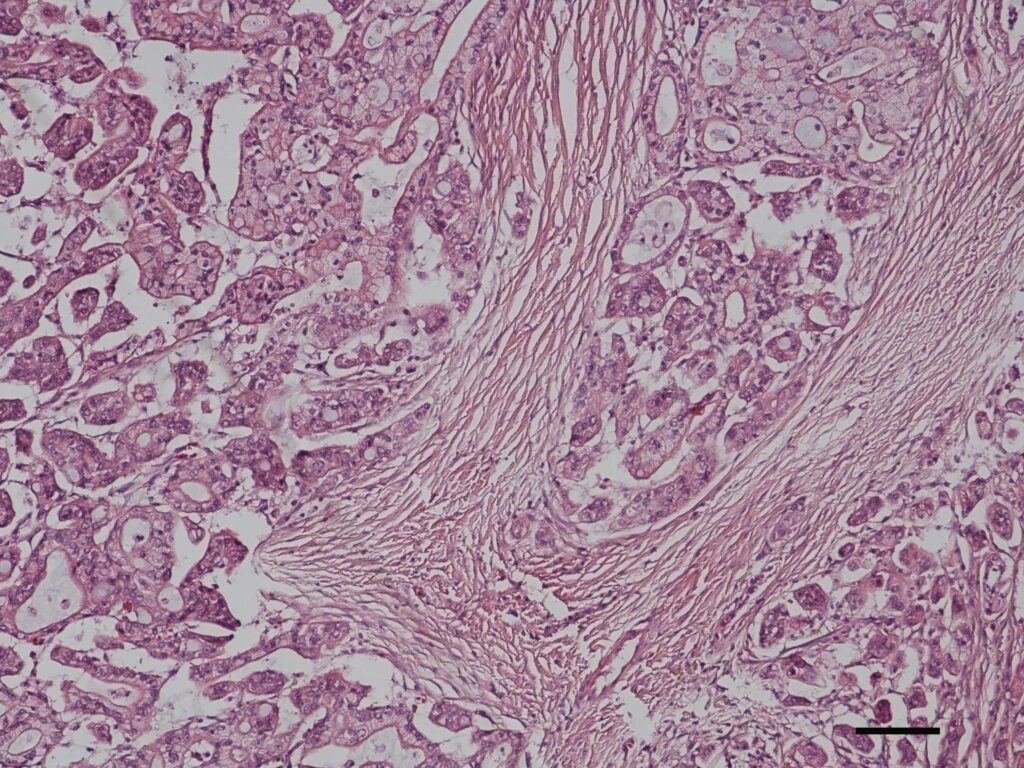

- Fig. 4: Histological picture of a highly aggressive, tubulopapillary prostate carcinoma with infiltrative growth (Gleason Pattern 3, score sum 8, bar = 100 µm)

No gender or age predisposition for BRAF mutation could be shown in this study. There was also no correlation between the detection of BRAF mutation and the invasivity or aggressiveness of TCC in dogs (GRASSINGER et al. 2019).

In a small study (n=10), carcinomas of the kidney tubules did not show BRAF mutation. However, two of six carcinomas of the transitional epithelium of the renal pelvis were positive (AUPPERLE-LELLBACH et al. 2019).

BRAF mutation in canine prostate carcinoma (PCa)

For canine PCa (Fig. 3) as well, detection of BRAF mutation from different materials could be established (GRASSINGER et al. 2019).

Possible sample materials:

- tissue (e.g. biopsies)

- cytological smears (e.g. FNA)

Again, specificity was 100% as the mutation could neither be detected in samples with benign prostatic hyperplasia, squamous epithelial metaplasia, atrophy of the prostate nor in normal prostate tissue.

Sensitivity of BRAF mutation detection in canine PCa was 61%.

Based on a histological score, prostate carcinomas caused by BRAF mutation (Fig. 4) were much more aggressive than those not caused by this mutation (GRASSINGER et al. 2019).

Conclusion

BRAF mutation testing is a highly specific method (100%) for the detection of canine transitional cell and prostate carcinoma.

Sensitivity, however, varies depending on the site (kidney, urinary bladder, urethra, prostate gland) and possibly the breed:

Transitional cell carcinoma:

86% long- and short-legged terrier

44% other breeds

Prostate carcinoma: 60%

Testing for BRAF is indicated in cases in which

- invasive sampling should be avoided,

- the cytological/histological result is not conclusive.

Only a positive result confirms a carcinoma.

If no BRAF mutation is detected in the sample, it may be because of the following reasons:

- There is no TTC/PCa (e.g. polyp, benign hyperplasia).

- The carcinoma is not caused by the BRAF gene mutation.

- There are no mutated cells in the sample, even though a carcinoma is present (representativeness of the sample, cytology/urine low in cells).

BRAF mutations in feline urinary bladder carcinoma

We examined biopsies of 25 cats with TCC (n=19), urinary bladder polyp (n=2) or cystitis (n=4) for the presence of BRAF mutation (HOHLOCH et al. 2019). There was no mutation detected in any case!

Thus, BRAF mutation analysis is not suitable for the diagnosis of transitional cell carcinoma in cats.