The gold standard in the diagnosis of mast cell tumours (MCT) is cytology and histopathology. Clinical staging is based on the clinical picture including the lymph node status (cytological/ histological). Immunohistological and molecular genetic methods are also available for more precise characterisation.

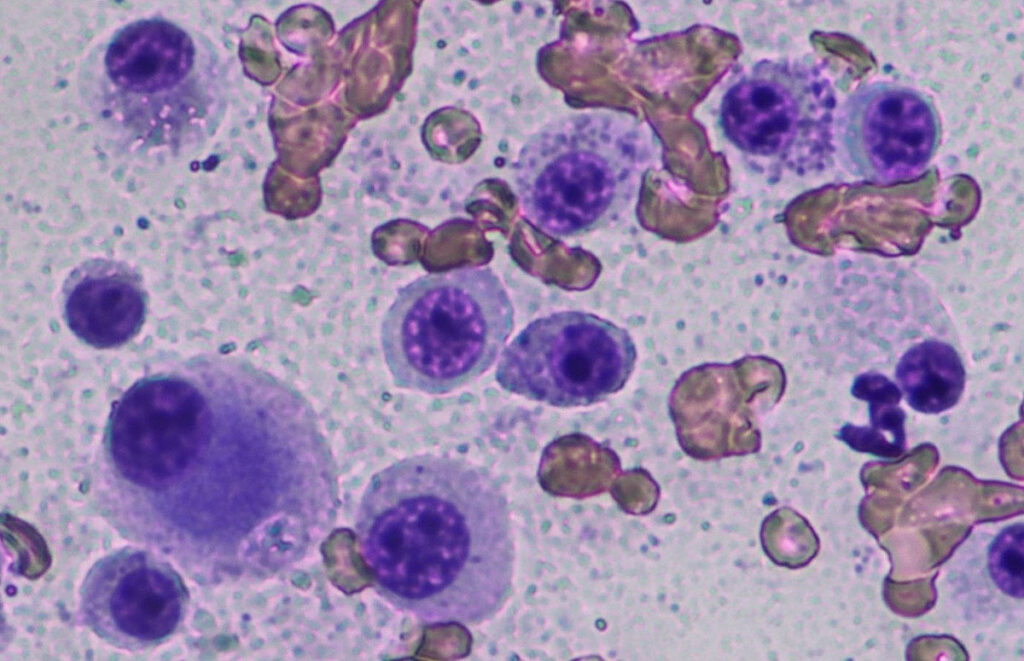

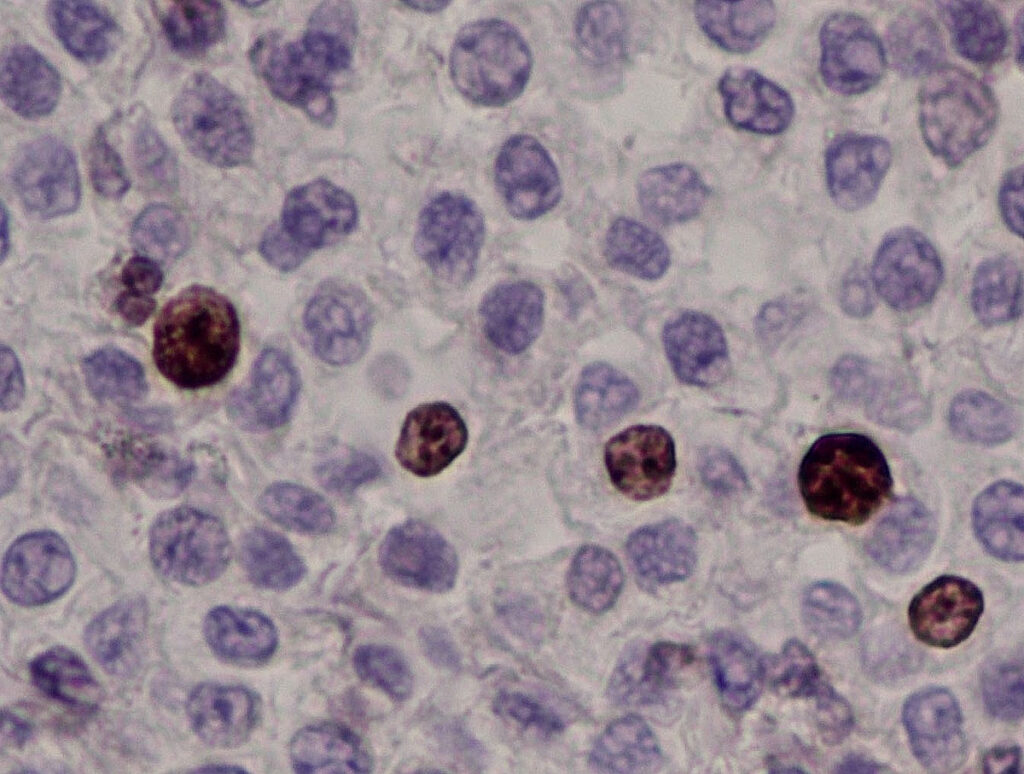

Cytology is used for preoperative diagnosis (Fig. 1) and clinical staging (e.g. lymph nodes, spleen). Although cytological grading of canine mast cell tumours has been published (Blackwood et al. 2012), it has limitations, as the cytological malignancy criteria are often overestimated with subcutaneous MCT not being identified.

Histopathology can be used to distinguish cutaneous from subcutaneous mast cells and assess the resection margins. Histological grading enables a statement to be made regarding the biological behaviour (probability of recurrence, risk of metastasis, survival times) of cutaneous mast cell tumours in dogs.

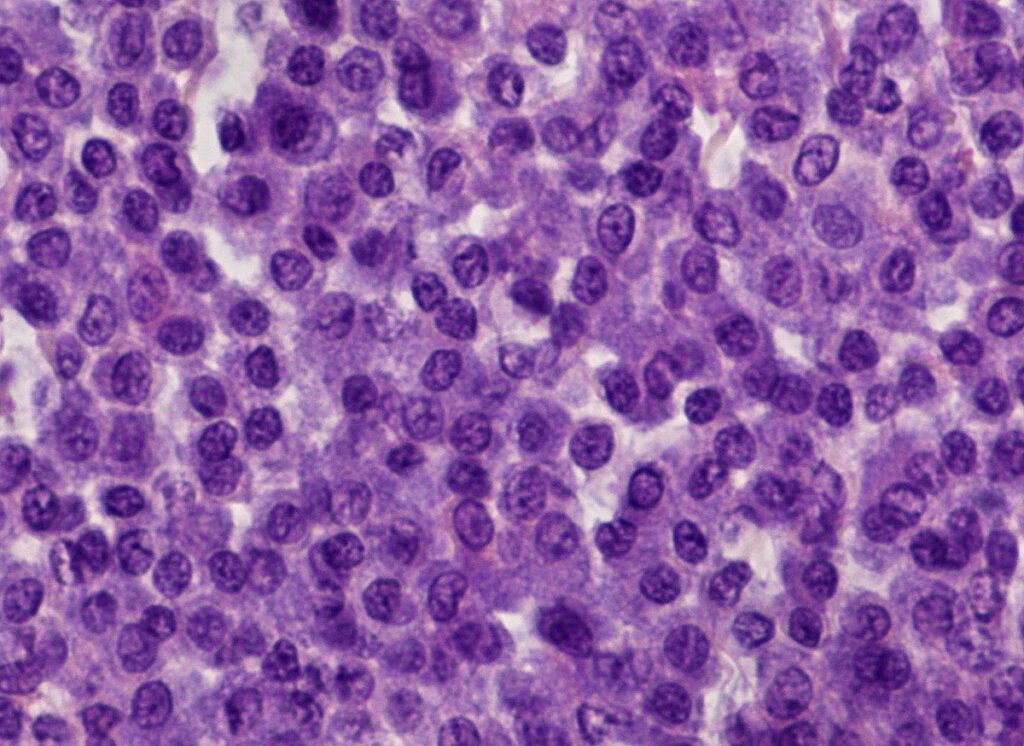

There are two histopathological grading systems for cutaneous mast cell tumours in dogs: The older grading system according to Patnaik et al. (1984) distinguishes between three tumour grades (grade I well differentiated – Fig. 2 -, grade II moderately differentiated and grade III poorly differentiated). It is based on the following criteria, among others: tumour loca- lisation, cell morphology, nuclear morphology, overall architecture and number of mitoses. As this system contains several criteria that are not easy to objectify, a modified two-stage system was established that is based on parameters that are easier to measure (Kiupel et al. 2011). In accordance with the recommendations of the consensus group (Berlato et al. 2021), a combination of both grading systems is currently usually specified, which correlate with prognostic statements (see Table 1) (Stefanello et al. 2015).

If a mast cell tumour is subcutaneous, the grading systems according to Patnaik et al. (1984) and Kiupel et al. (2011) should not be used, as subcutaneous MCTs are generally less malignant than cutaneous MCTs (Bellamy and Berlato 2022). With a few exceptions, they can generally be well controlled locally and usually require no further treatment once they have been completely removed (Betz 2021).

Table 1: Prognostic statements for cutaneous mast cell tumours in dogs, based on the combined grading systems of Patnaik et al. (1984) and Kiupel et al. (2011) – modified according to Stefanello et al. (2015)

| Grading | Prognosis | Tumour-related deaths | Risk of lymph node metastases | Risk for distant metastases |

| Grade I / low-grade | good | rare | 6 % | 2 % |

| Grade II / low-grade | mostly good | 3 % to 17 % of dogs die as a result of the mast cell tumour. | 16 % | 2 % |

| Grade II / high- grade | cautious | 14% to 56% of dogs die as a result of the mast cell tumour.

Median survival time: 7.5 to 23.3 months |

15 % | 2 % |

| Grade III / high- grade | very cautious to unfavourable | 67 to 75 % of dogs die as a result of the mast cell tumour.

Median survival time: 3.6 to 6.8 months |

46 % | 21 % |

Furthermore, lymph nodes can be examined histologically for a neoplastic tumour cell population. The assessment is based on the scheme by Weishaar et al. (2014). The prognosis is significantly better in stages HN0/HN1 than in HN2/HN3.

HN0: None to isolated (0-3 mast cells/HPF), scattered and solitary mast cells in the sinus (subcapsular, paracortical or medullary) and/or in the parenchyma. Assessment: no metastatic infiltration (reactive or normal).

HN1: More than 3 scattered and solitary mast cells in the sinus (subcapsular, paracortical or medullary) and/or parenchyma in at least 4 HPF. Assessment: pre-metastatic (grey area).

-

Fig. 1: Cytology: poorly differentiated mast cell tumour

Image source: Laboklin

-

Fig. 2: Histopathology: cutaneous mast cell tumour grade I according to Patnaik et al. 1984, low-grade according to Kiupel et al. 2011

Image source: Laboklin

-

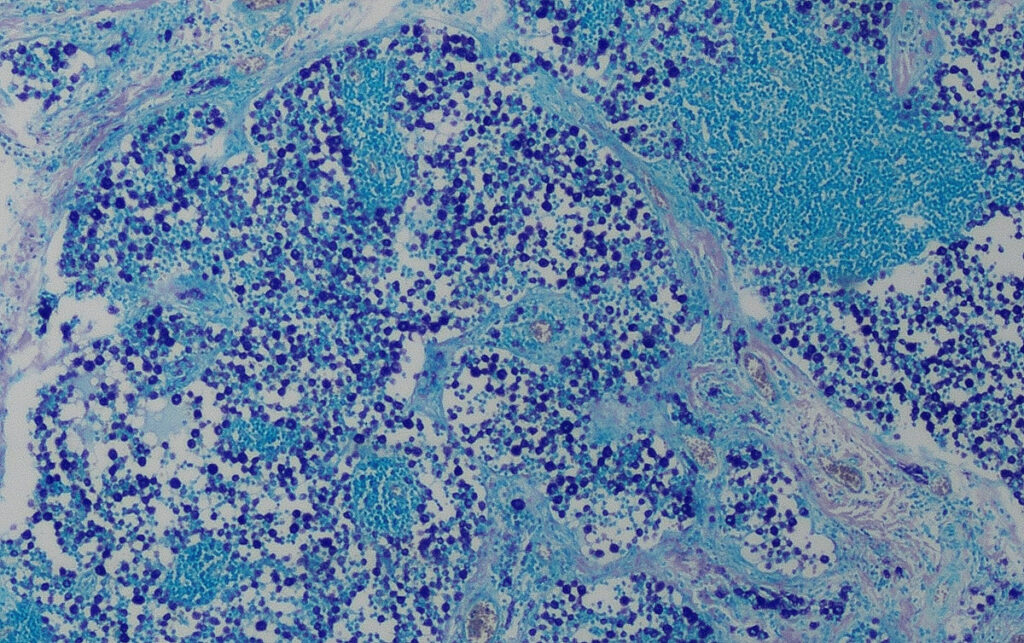

Fig. 3: Histology (Giemsa stain): heavy infiltration of the lymph node with mast cells, stage HN3

Image source: Laboklin

-

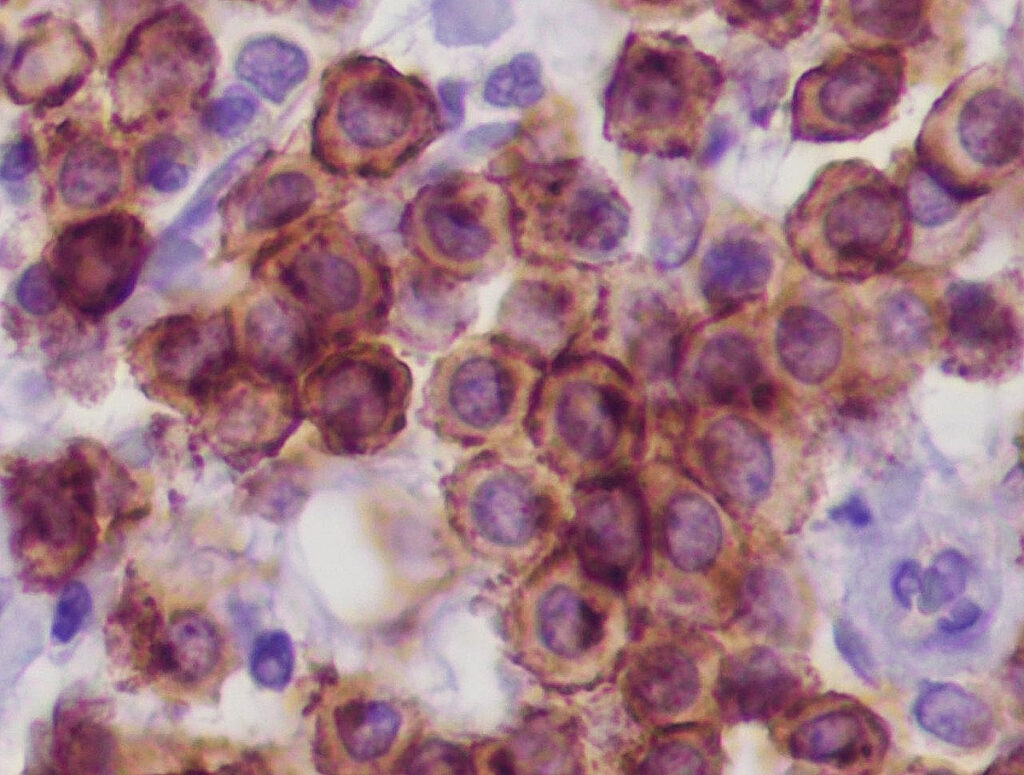

Fig. 4a: Immunohistology cKIT: regular membranous expression pattern of mast cells

Image source: Laboklin

-

Fig. 4b: Immunohistology Ki-67 antigen: The nuclei of individual mast cells react positively (brown).

Image source: Laboklin

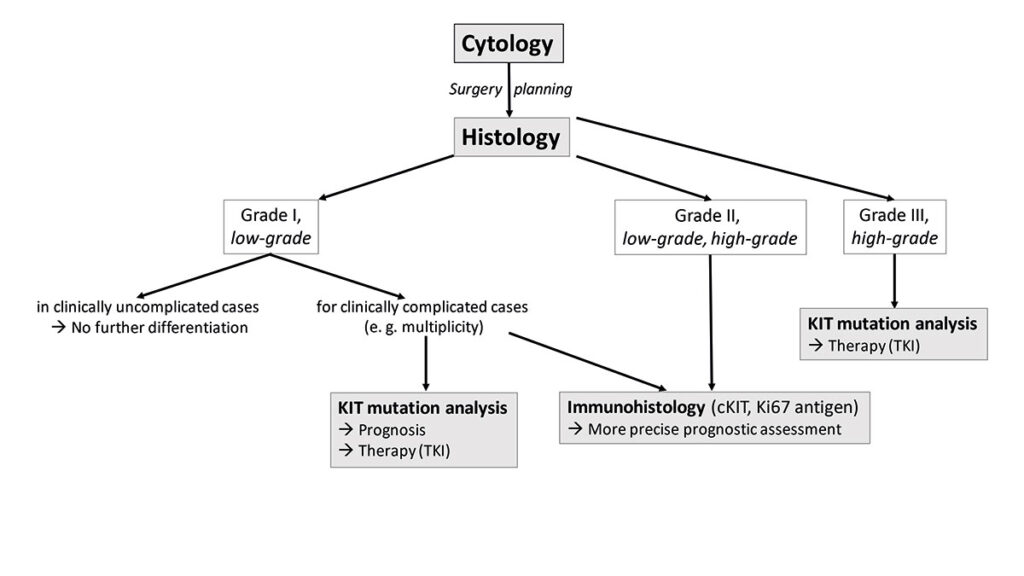

- Fig. 5: Diagnostic algorithm of cutaneous canine mast cell tumours

HN2: Aggregates (clusters) of mast cells (> 3 associated cells) in the sinus (subcapsular, paracortical or medullary) and/or parenchymal or sinusoidal accumulations of mast cells. Assessment: early stage of metastasis.

HN3: Destruction of the normal lymph node architecture by discrete lesions, nodules or larger masses of mast cells (Fig. 3). Assessment: overt metastasis.

In addition, immunohistological examinations are also possible for canine mast cell tumours. The distribution pattern (membranous, perinuclear or diffuse) of the receptor tyrosine kinase KIT (cKIT, Fig. 4a) (Freytag et al. 2021; Da Gil Costa et al. 2011) and the number of tumour cells expressing Ki-67 antigen (Fig. 4b) provide information about the degree of differentiation or proliferation activity of the MCT. The immunohistological results only have prognostic (not therapeutic) relevance. The detection of an atypical cKIT expression pattern (type 2 or 3) is correlated with a poorer prognosis (Freytag et al. 2021). More than 23 Ki-67 positive cells/1 ocular grid area are associated with a shorter survival time (Webster et al. 2007). However, there is no reliable data for some combinations of results (e.g. cKIT pattern type 1 and a high number of Ki-67 antigen positive tumour cells at the same time). There is no correlation between the immunohistological cKIT expression pattern and the presence of a KIT gene mutation or the response to treatment with tyrosine kinase inhibitors!

A mutation of the KIT gene, which leads to hyperactivity of the tyrosine kinase receptor KIT and to ligand-independent mast cell proliferation, can be detected by molecular genetics.

Based on this pathogenesis, tyrosine kinase inhibitors such as toceranib phosphate and masitinib are used for non-resectable mast cell tumours in dogs. The response of the tyrosine kinase inhibitor masitinib is significantly better in the presence of a KIT mutation in exon 11 than in the wild type. However, this does not mean that there is no therapeutic effect of tyrosine kinase inhibitors in the absence of a mutation (Hahn et al. 2008).

The detection of a KIT mutation in exon 11 in cutaneous mast cell tumours is significantly correlated with a shorter survival time. Mast cell tumours with a mutation in exon 8 are presumably less aggressive. Detection of the KIT mutation therefore serves to improve prognosis assessment and individualised treatment planning (Nardi et al. 2022; Bellamy and Berlato 2022; Thamm et al. 2019).

However, due to the enzymes in the mast cell granules, fixation and embedding in paraffin (both in smears and histological samples), it is not always possible to isolate DNA of sufficient quality for sequencing.

Subcutaneous mast cell tumours with a KIT mutation in exon 11 are more likely to be histologically high-grade and have a higher mitotic count (Chen et al. 2022).

Conclusion

In summary, it should be pointed out once again that the histological grading, the immunohistological results and the c-Kit mutation status of a cutaneous mast cell tumour are only some of many prognostic factors that correlate with the clinical course of the disease. Depending on the situation of the case, different further investigations are useful (Fig. 5). However, numerous other clinical parameters and the anatomical location of the mast cell tumour must be included in the final assessment of each individual case (Willmann et al. 2021; Blackwood et al. 2012).

PD Dr. Heike Aupperle-Lellbach

Range of services

Cytology

Pathohistology

Pathohistology with increased effort

c-Kit-mutation

Immunohistological examination