Feline patients with respiratory infections are common in companion animal practice. The clinical signs associated with these infections are diverse, ranging from mild nasal discharge to severe pneumonia.

The primary etiological agents implicated in these cases are five pathogens that comprise the feline upper respiratory tract disease (URTD) complex: feline herpesvirus 1 (FHV-1), feline caliciviruses (FCV), Chlamydia felis, Bordetella bronchiseptica and Mycoplasma felis. These pathogens can cause single or mixed infections in affected cats.

In addition to these primary URTD pathogens, secondary bacterial infections can also occur, particularly in cases of severe or protracted illness. Those can further complicate the clinical presentation and may necessitate additional therapeutic interventions.

For the detection of viruses polymerase chain reaction (PCR) is the method of choice, whereas bacterial pathogens can also be identified via bacterial culture (BC). Indirect detection using antibodies is less appropriate, since many patients are either vaccinated or have an unknown vaccination status. Additionally, in case of an acute infection, antibodies may not yet be detectable.

According to various studies most URT infections have a viral origin (i. e. FHV-1/ FCV-1). An infection with FHV-1 typically leads to a lifelong latency, with affected animals experiencing recurrent infection, especially during periods of stress or immunosuppression. The clinical signs can range from rhinitis, conjunctivitis, keratitis and fever to severe pneumonia. FCV infections can lead to a range of symptoms, from typical ulcers in the oral cavity to infections of the upper respiratory tract, fever and arthritis. This variability in symptoms is due to the high mutation rate of the virus, which results in differing levels

of virulence.

According to the literature, Mycoplasma felis, Chlamydia felis, Bordetella bronchiseptica and, less commonly, Streptococcus (S.) canis and Streptococcus (S.) equi ssp. zooepidemicus have been detected in cats with URTD even in the absence of FHV-1 or FCV, suggesting that these agents may also play a primary role. In a study by Veir et al. (2008), approximately 80% of nasal/pharyngeal swabs from cats with respiratory symptoms were positive for Mycoplasma felis, while this pathogen was rarely detected in samples from healthy cats.

Symptoms of an infection with Mycoplasma felis or Chlamydia felis can range from conjunctivitis, keratitis and fever to severe pneumonia, although the latter is rare. Both agents are also associated with reproductive problems. Chlamydial infections are common in kittens. PCR is the method of choice for routine diagnosis of mycoplasma and chlamydial infections. Bordetella bronchiseptica plays a less significant role in cats and is more commonly associated with lower respiratory tract infections. These bacteria can be detected not only using PCR, but bacterial culture, bringing the advantage of performing an antimicrobial susceptibility test afterwards.

-

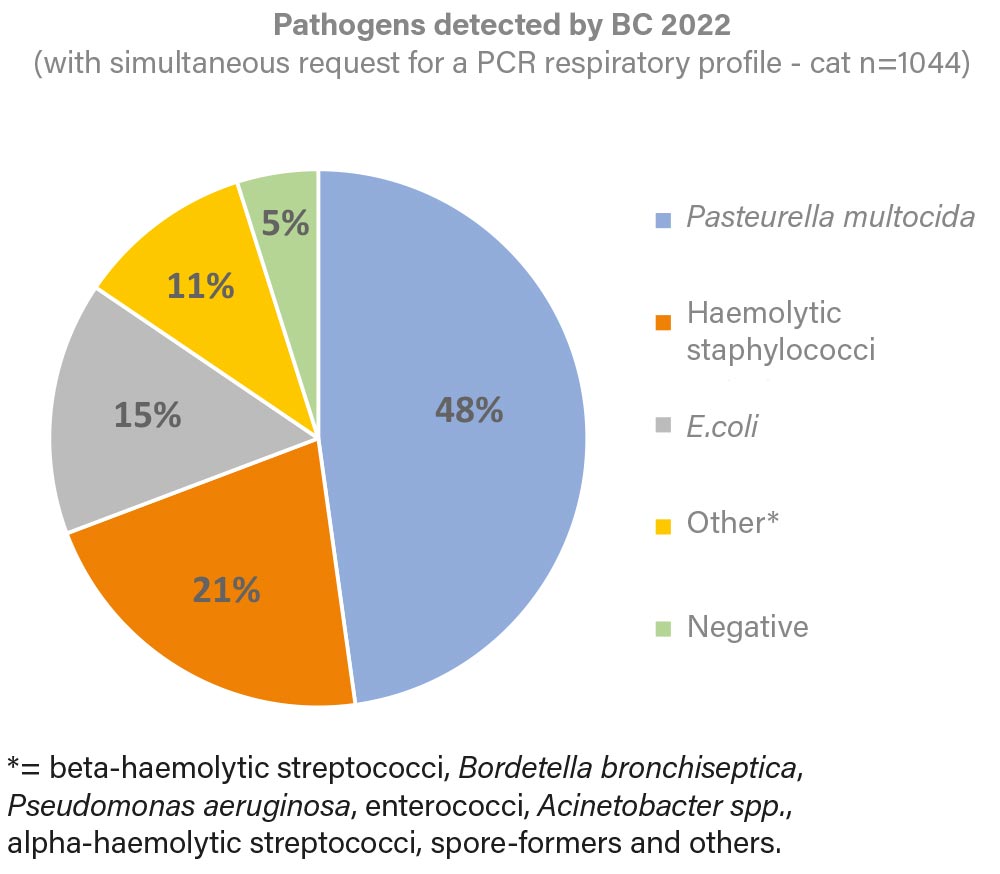

Fig. 1: Pathogens detected by BC in 2022 (with simultaneous request for a PCR respiratory profile of the cat)

Image source: Laboklin

-

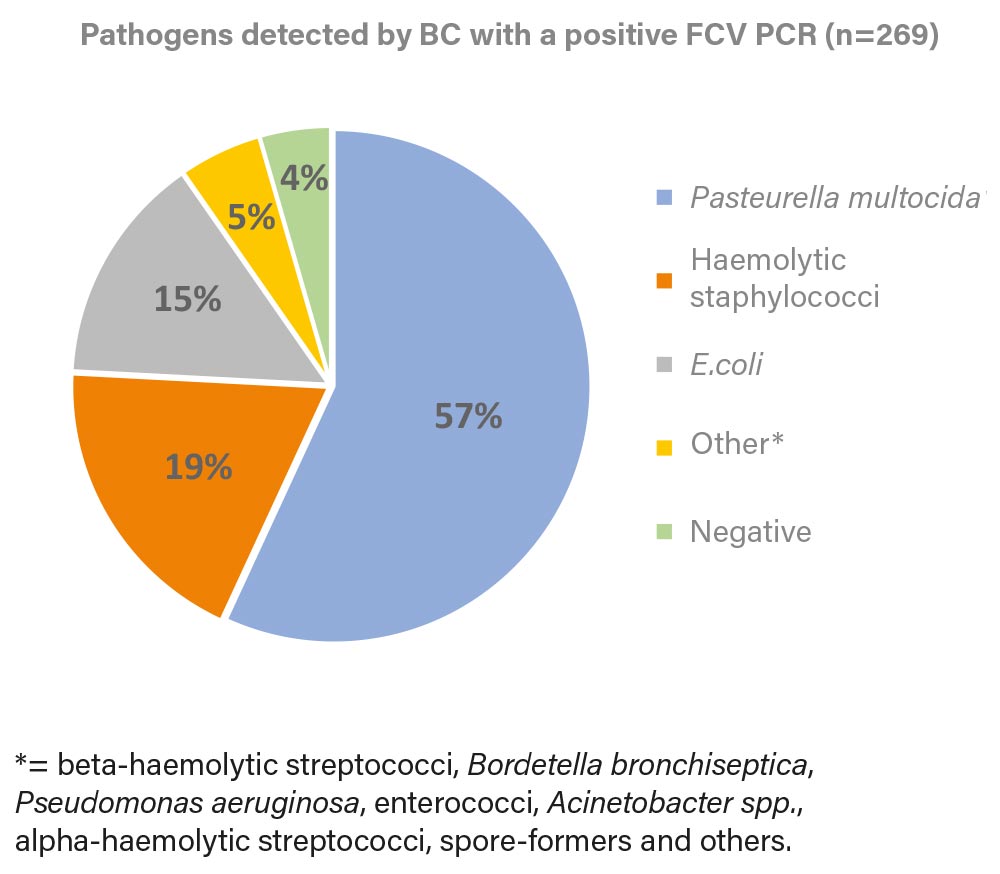

Fig. 2: Pathogens detected by BC in a positive FCV PCR (2022)

Image source: Laboklin

-

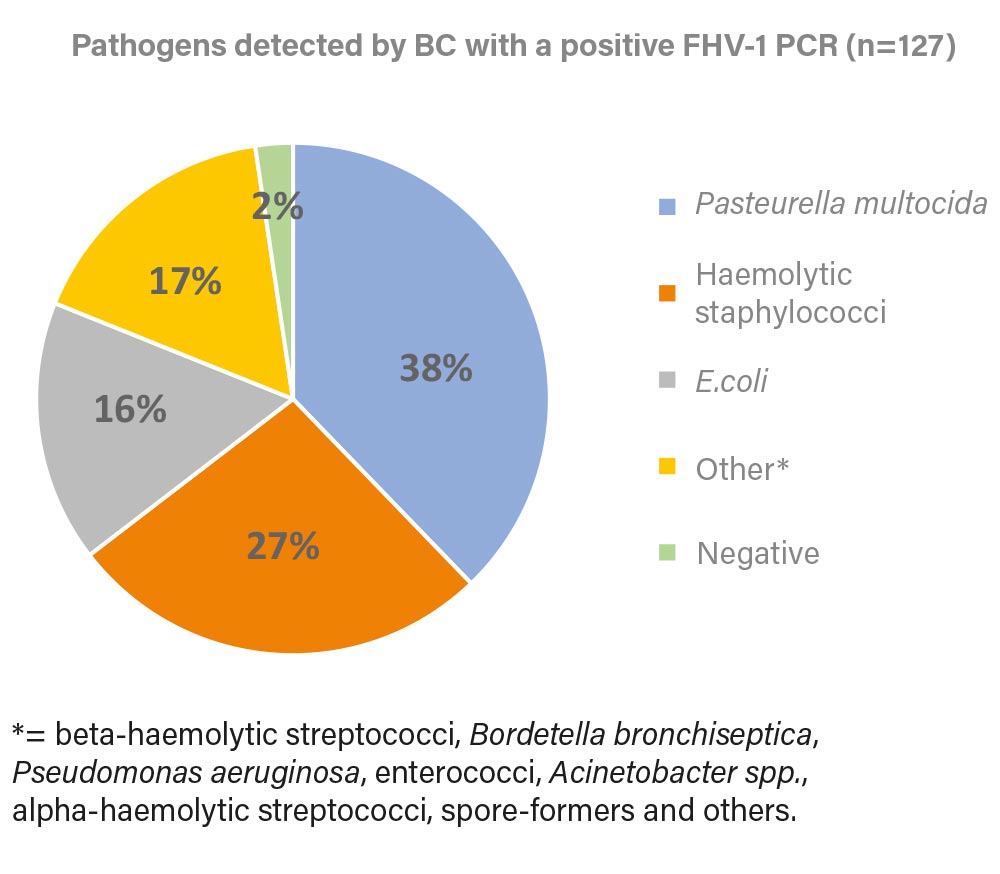

Fig. 3: Pathogens detected by BC in a positive FHV-1 PCR (2022).

Image source: Laboklin

Tip: It is important to obtain swabs without transport medium (from the eye/oral cavity and/or throat) for PCR and swabs with transport medium (from the same locations) for bacterial culture before starting treatment in patients suspected of having URTD to ensure comprehensive diagnosis.

S. canis and S. equi ssp. zooepidemicus are described as commensals of the mucosal surfaces of healthy cats. Under certain conditions, such as stress, high infection pressure or immunosuppression, these agents can also cause primary diseases ranging from sinusitis to pneumonia, especially in larger groups of cats (breeding facilities, animal shelters). S. equi ssp. zooepidemicus gained attention after an outbreak in a shelter in Israel in 2010, where it was isolated from a large proportion of deceased cats with purulent nasal discharge, cough, sinusitis, dyspnea and pneumonia. Both species mentioned above belong to the beta-haemolytic Streptococcus group and can be cultured easily. They also play a role as secondary agents, as do Staphylococcus spp., Pasteurella multocida and Escherichia coli (E. coli).

Tip: Additionally, testing for FeLV (Feline Leukemia Virus) and FIV (Feline Immunodeficiency Virus) status is useful, because animals with retroviral infections are often predisposed to URT infections and may have more severe courses of disease.

Lower respiratory tract infections (bronchitis/pneumonia) can also arise secondarily from upper respiratory tract infections. Furthermore, bacterial secondary infections are common even in non-infectious primary causes (e.g., anatomical problems of the larynx/trachea, allergies). However, primarily Bordetella bronchiseptica and Mycoplasma felis have been described here, which can lead to chronic bronchopneumonia/bronchitis. Clinically, bronchitis is usually manifested by coughing. Bronchoalveolar lavage (alternatively: tracheal wash) should be performed in this case. Both secretions can be used for PCR as well as bacterial culture.

Patients showing symptoms of cough, fever, lethargy, and anorexia may suffer from pneumonia. Pneumonia is very rarely caused by bacterial infections or the classical feline respiratory viruses, but is more often caused by aspiration, injuries, or underlying conditions such as diabetes mellitus. Bacterial infections are much more commonly secondary at this stage. The responsible pathogens are equivalent to those causing URT infections.

| Pathogen (name of the PCR profiles) | total (n) | PCR positive (n) | PCR positive (%) |

| FHV (respiratory tract I-IV) |

7676 |

851 |

11 |

| FCV (Airways I-IV) |

7676 |

2127 |

28 |

| Chlamydia (respiratory tract I-III) |

7053 |

413 |

6 |

|

Mycoplasma felis (respiratory tract I+II) |

6607 |

3007 |

46 |

| Bordetella bronchiseptica (respiratory I) |

3718 |

104 |

3 |

Table 1: Detection frequency of the 5 primary pathogens of the feline rhinotracheitis complex by PCR (respiratory profiles I-IV) in 2022

Source: Laboklin

In 2022, we evaluated 7676 respiratory PCR profiles (PCR profiles I-IV), each containing the five primary feline respiratory pathogens in various combinations. FHV-1 and FCV were identified as the most important primary pathogens, represented in all of the five profiles. FCV was detected in 28% and FHV-1 in 11% of all tests. Chlamydia was detected in 6% of the samples, whereas Mycoplasma felis was found in 46%. Only 3% of the samples were tested positive for Bordetella bronchiseptica (Table 1). Infections occured either as single or combined infection.

In addition to PCR profiling, bacterial culture (BC) was requested in 1044 cases (Figure 1). In these examinations, the most frequently detected pathogens were Pasteurella multocida (48%), haemolytic staphylococci (21%) and E. coli (15%), which could be isolated individually or in combination. Only 5% of the bacterial culture showed no bacterial growth (negative).

When performing both bacterial culture and one of the four respiratory profiles (n=645),

62% of the samples were positive for at least one of the 5 PCRs (FHV-1, FCV, Chlamydia, Mycoplasma felis, Bordetella bronchiseptica). Of these 645 samples, 42% were positive for FCV and 20% were positive for FHV-1. Using these two primary pathogens as an example, we investigated which bacterial pathogens could be identified in bacterial culture (Figure 2

and 3).

Beta-haemolytic streptococci, including S. canis and S. equi ssp. zooepidemicus, which are among the possible primary pathogens in URTD, were detected rarely and therefore summarised under “Others”, the same applies to Bordetella bronchiseptica.

Identical to Figure 1 Pasteurella multocida, haemolytic staphylococci and E. coli were identified as the most common pathogens. In combination with the primary viral pathogens, these bacteria often require therapy.

Conclusion:

PCR is the method of choice for detecting the five most important primary pathogens in cats with respiratory infections, as it is reliable and fast. Bacterial culture is also useful in most cases to identify secondary infections that require antibiotic therapy and to treat them successfully using an antibiogram. Especially in case of chronic respiratory problems or lower respiratory problems both investigations are recommended. To be emphasised are a detailed anamnesis, appropriate sample material, and the interpretation of the test results in the context of the clinical presentation.

Dr. Eva-Maria Klas

Dr. Marie-Louise Hoffknecht

Further reading

-

Lappin MR, Blondeau J, Boothe D, Breitschwerdt EB, Guardabassi L, Lloyd DH, Papich MG, Rankin SC, Sykes JE, Turnidge J, Weese JS. Antimicrobial use Guidelines for Treatment of Respiratory Tract Disease in Dogs and Cats: Antimicrobial Guidelines Working Group of the International Society for Companion Animal Infectious Diseases. J Vet Intern Med. 2017;31(2):279-294. doi: 10.1111/jvim.14627.

-

Veir JK, Ruch-Gallie R, Spindel ME, Lappin MR. Prevalence of selected infectious organisms and comparison of two anatomic sampling sites in shelter cats with upper respiratory tract disease. J Feline Med Surg. 2008;10(6):551-7. doi: 10.1016/j.jfms.2008.04.002.

-

Greene CE, Prescott JF. Streptococcal infections. In: Greene CE, editor. Infectious diseases of the dog and cat. California, USA. 4th ed. Elsevier, 2012, pp 325–333.