Liver disease is a common problem in horses. Increased liver enzyme activities are often detected incidentally or may be identified in patients showing non-specific clinical signs. In an evaluation of 817 serum samples analysed at Laboklin in autumn 2023, nearly 20% of the horses showed mildly elevated γ-GT values ranging from 50 to 150 U/l (Reference: <44 U/l). In almost 7% of

the cases, increased serum bile acid levels above 12 μmol/l were also observed. To evaluate the underlying cause of these alterations, it is important to interpret the values correctly and, if necessary, initiate further diagnostic investigations.

Introduction

The liver plays a role in several metabolic processes, including the metabolism of proteins, carbohydrates, and fats; the production of coagulation factors and bile; as well as the synthesis and storage of vitamins and the excretion of metabolic waste products, toxins, and drugs. Due to its diverse roles, the liver is exposed to various noxious agents that can lead to hepatic damage.

-

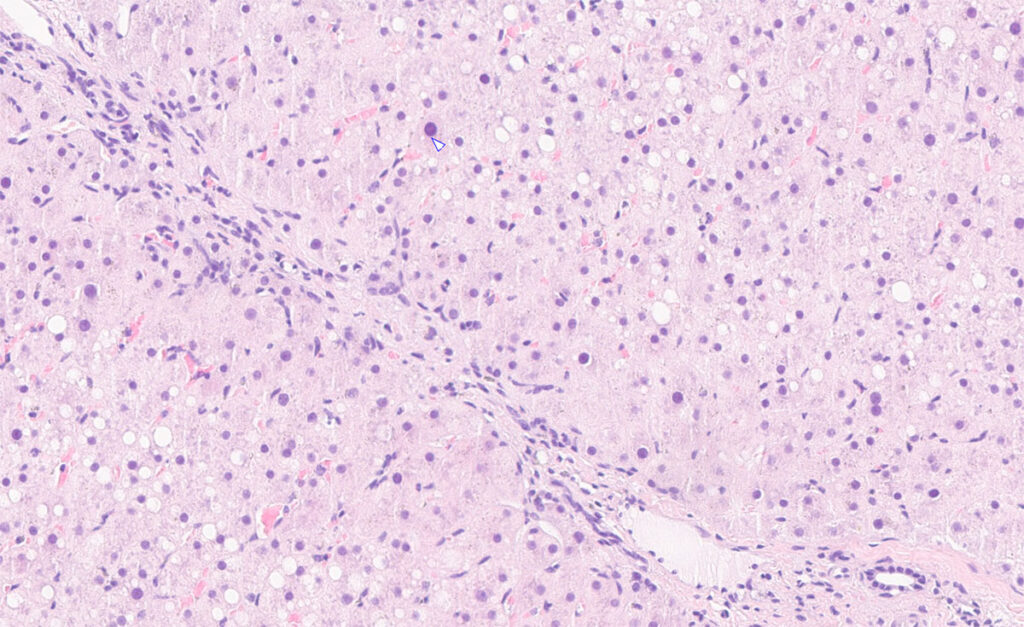

Fig. 1: Liver biopsy of a horse with long-term exposure to mycotoxins and suspected poisonous plants: mild to moderate fibrosis.

Image source: Laboklin

Clinical Signs of Liver Disease

A large proportion of liver diseases are subclinical. This is due to the liver’s substantial capacity for cellular regeneration. Liver failure occurs only when the loss of hepatocyte function exceeds their regenerative capacity, which generally requires damage to around 80% of the organ. This highlights the importance of recognising and interpreting non-specific clinical signs at an early stage, such as lethargy, inappetence, icteric sclerae and mucous membranes, weight loss, reduced performance, or episodes of colic. Early identification of a mild hepatopathy is associated with a positive prognosis.

More severe signs include hepatic encephalopathy, hepatocutaneous syndrome, bleeding tendency, photosensitivity, and diarrhoea.

Diagnostics

The laboratory diagnostic evaluation of liver diseases in horses is primarily based on the interpretation of liver-specific enzyme activities and functional parameters in serum. Additional laboratory results provide valuable information on the extent of liver damage as well as on possible underlying systemic diseases. Often, further investigations such as sonography and liver biopsy are required to clarify the aetiology (Fig. 1).

Blood Tests – Enzymes

Blood tests often provide the first indications of liver disease through the detection of elevated liver enzyme activities. The parameters are distinguished according to their localisation within the liver (hepatocellular, biliary). They can also be classified based on whether they are liver-specific or ubiquitous.

1. Hepatocellular Enzymes

a. Glutamate dehydrogenase (GLDH)

GLDH is an enzyme specifically found in hepatocytes. It is rapidly released into the serum during acute, cellular liver damage.

Due to its short half-life (approximately 14 hours, with complete decline after 3–5 days), it is particularly useful for detecting acute hepatocellular damage and is considered the most sensitive marker.

b. Aspartate aminotransferase (AST)

AST is not liver-specific, as it is present not only in hepatocytes but also in muscle cells and erythrocytes. Isolated elevations should always be interpreted in the context of GLDH, creatine kinase (CK), and LDH.

c. Lactate dehydrogenase (LDH)

LDH is present in numerous tissues, including cardiac and skeletal muscle as well as erythrocytes. Because of this widespread distribution, its diagnostic value for the liver is meaningful only when interpreted alongside other enzymes.

2. Biliary Enzymes

a. γ-Glutamyltransferase (γ-GT)

γ-GT is a liver-specific enzyme with a half-life of 3–4 days, although in some cases it may remain elevated for several weeks. This enzyme is mainly produced in the bile duct epithelium. Increased serum activity occurs primarily in cholestasis and biliary diseases. While also present in the kidney and pancreas, it is mainly liver-specific. In sport horses, isolated γ-GT elevations (>50–150 U/l) can occur during intensive exercise.

b. Alkaline phosphatase (AP)

AP also shows increased activity in cholestatic processes but is less organ-specific, as it is present in bone, placenta, and intestine. In young animals, elevated AP due to bone growth should be considered physiological.

Proper interpretation of values is essential to guide further diagnostics or determine the optimal timing for re-testing. For γ-GT, in cases of mild elevation (Table 1), re-evaluation after 2–4 weeks, possibly including additional herd mates, is recommended to clarify a toxic or infectious aetiology and to assess disease progression.

Table 1: Classification of liver enzyme elevation by degree

| Degree of Elevation | |

| Mild | 2–3 × upper cut-off |

| Moderate | 4–5 × upper cut-off |

| High | 10 × upper cut-off |

Blood Tests – Liver Function

Changes in liver enzyme levels provide only limited information on disease severity, prognosis, or aetiology. Additional liver function parameters can help to better assess the extent of damage and prognosis. Bile acids constitute the primary parameter for assessment.

- Bile Acids

Bile acids are produced in hepatocytes, continuously secreted into the duodenum, and 90–95% are reabsorbed. When cell function is impaired, reabsorption is reduced or absent, leading to accumulation and increased serum concentrations. Values above 25 μmol/l are regarded as pathological and indicate a poor prognosis in chronic cases. In acute cases, high values are of less prognostic concern, but require close surveillance. Bile acids are a highly sensitive marker for functional liver insufficiency, particularly in chronic diseases. - Bilirubin

Bilirubin is derived from degradation of haemoglobin, conjugated in the liver, and excreted via bile. Values above 75 μmol/l are associated with the characteristic yellow discoloration of the sclera and mucous membranes (icterus, jaundice). Differentiating between conjugated and unconjugated bilirubin in the blood allows the cause to be classified as pre-hepatic, intra-hepatic, or post-hepatic.

A conjugated fraction of more than 25% indicates a hepatocellular or hepatobiliar origin. In chronic conditions, however, serum bilirubin concentrations may remain within the normal range. - Ammonia

Elevated blood ammonia levels indicate advanced liver insufficiency and can lead to hepatic encephalopathy. Measurement is challenging due to its low stability (maximum 30 minutes).

Imaging / Biopsy

Ultrasonography of the liver is a useful supplementary diagnostic tool, even if only a portion of the organ is accessible for imaging due to anatomical reasons. Although many changes are diffuse, ultrasonography can still provide valuable information. The absence of pathological findings does not rule out liver disease. Liver biopsies are indicated when clinical signs and laboratory values do not allow a definitive diagnosis. Samples can be submitted for histology, bacteriology, and pathogen detection via PCR.

Aetiology

Intoxication

Intoxications are among the most common causes of hepatopathies. They can arise from, for example, mycotoxins or moulds in roughage, microcystins from algae-contaminated water, or excessive iron intake.

Particular attention should be paid to poisonous plants in pastures and hay. Although horses usually avoid them, ingestion can occur under certain conditions (e.g. in young animals, during feed shortages, in the presence of exotic plants, or when plant parts are fragmented).

Species of Senecio, such as ragwort, can lead to altered liver enzyme activities even in the early stages of intoxication, often without clinical symptoms. The toxic agents are pyrrolizidine alkaloids (PAs), which can cause irreversible liver fibrosis with chronic exposure.

LC-MS analysis of urine allows detection of senecionine/senecionine-N-oxide and indicates toxin exposure in the preceding hours to days. Additionally, roughage analysis (e.g., through agricultural testing facilities) is recommended.

Infections

Viruses

Viral hepatitis in horses is increasingly well studied. Of particular relevance are equine hepacivirus (EqHV) and equine parvovirus-hepatitis virus (EqPV-H).

EqPV-H is associated with Theiler’s disease – an acute hepatitis with fulminant liver necrosis and usually fatal outcome. Transmission is likely via blood products (e.g., tetanus antitoxin, stem cell products, equine plasma), and possibly via vectors. The virus is widespread worldwide, with seroprevalences in healthy horse populations (e.g., Germany, Austria) ranging between 15% and 34.7%, though only about 2% develop clinical disease. EqPV-H should be considered in the differential diagnosis when relevant symptoms are present.

EqHV, first described in 2012, can cause acute or chronic persistent infections. Symptoms range from weight loss, anorexia and jaundice to neurological abnormalities.

Both viruses are detectable by PCR in blood or liver tissue during the acute stage. Histopathological examination of liver biopsies can additionally help to assess the severity and prognosis of liver damage.

Bacteria

Bacterial liver disease is rare and usually secondary. When it occurs, it is often severe. It typically involves ascending bacterial infections, e.g., with Streptococcus equi or Staphylococcus aureus. In foals, liver abscesses can be caused by Rhodococcus equi and young animals may develop Tyzzer’s disease due to Clostridium piliforme. Clinically, bacterial hepatitis usually presents with jaundice, fever and colic. Pathogen detection can be performed on liver biopsy samples, which can be evaluated microbiologically and histologically. PCR-based detection is also an option.

Parasites

Parasitic liver damage occurs due to migrating stages of, for example, Strongylus spp. and Parascaris equorum. Liver fluke (Fasciola hepatica) is rare in horses but may occur in mixed pastures with ruminants or in wetland areas where water snails are present. Lesions can affect both liver parenchyma and bile ducts. In suspected cases, faecal samples can provide proof of infection; for some parasites (Fasciola hepatica, small strongyles/ small redworm), serology is more sensitive.

Conclusion

Hepatopathies are often detected late due to non-specific symptoms and subclinical cases. Diagnosis is based on the determination of liver enzyme activities and functional parameters, supported by diagnostic imaging techniques and, if necessary, liver biopsy. Toxic and infectious causes are most common, while environmental and dietary factors should also be considered when investigating the aetiology. Treatment efficacy is monitored through regular assessment of liver enzyme activities.

Recovery, however, can take weeks to months. As a preventive measure, depending on the aetiology, feed and pasture hygiene as well as evidence-based parasite control management can be helpful.

Dominika Wrobel-Stratmann, Dr. Svenja Möller,

Dr. Michaela Gentil

Our Services in Equine Liver Diagnostics

| Profile | Parameters | Sample Material |

| Liver 1 | AST, GLDH, γ-GT, bile acids | Serum |

| Liver 2 | GLDH, AST, AP, γ-GT, total bilirubin, cholesterol, urea, bile acids, protein, albumin, globulins, albumin/globulin ratio, glucose, Na, K, Cl | Serum and NaFB |

| Hepatotropic Viruses | PCR: equine parvovirus, equine hepacivirus | Serum, EDTA blood, liver tissue |

| Parasite Profile | Flotation, SAFC, modified McMaster method | Faeces |

| Coagulation | PT, PTT, thrombin time, fibrinogen | Citrate plasma |

| Bilirubin | Total and direct | Serum, EDTA plasma, heparin plasma |

| Single Analyses | ||

| Bile Acids | Serum | |

| Serum Protein Electrophoresis | Albumin, α-globulins, β-globulins, γ-globulins, total protein | Serum |

| Liver Fluke (Antibody Detection) |

|

Serum |

| Small Redworm Test (Antibody Detection) | Detects infection levels of all small redworm stages | Serum |

| Meadow Saffron | Colchicine | Urine |

| Ragwort | Senecionine, senecionine-N-oxide | Urine |

| Bacteriology | Aerobes, anaerobes | Swab with medium, tissue (native) |

| Histopathology | Tissue (fixed) | |