“The last child has fur” – this common social belief means that dogs often live very closely with people, like members of the family. As true specialists, endoparasites have developed strategies to adapt to different hosts through complicated development cycles and, thus, ensure their own survival. Travel and climate change have further expanded the range of potentially zoonotic worms, and dog owners as well as their children may be used as dead-end hosts. That is why we, as veterinarians, are also responsible for protecting human health, especially that of children, when it comes to combating endoparasites in animals.

Nematodes

The roundworms Toxocara canis and Toxascaris leonina can infect complete litters even if the female dog is dewormed regularly; this may already happen intrauterine or by galactogenic infection. The strategy of hypobiosis allows them to remain viable in the definitive host for years; hormonal changes during gestation lead to reactivation. Despite intensive control measures, and depending on age, prevalence rates of up to 30% in dogs and up to 19% in humans are reported.

In general, parasitoses impair the efficient use of nutrients, which, in puppies, mainly results in reduced growth and a shaggy, dull coat with scaling; diarrhoea and vomiting are other common signs. Leukocytes may increase and the activities of liver-specific enzymes may also be elevated. Intestinal third-stage larvae lead to mucosal lesions in the intestine resulting in protein loss (albumin and gamma globulins).

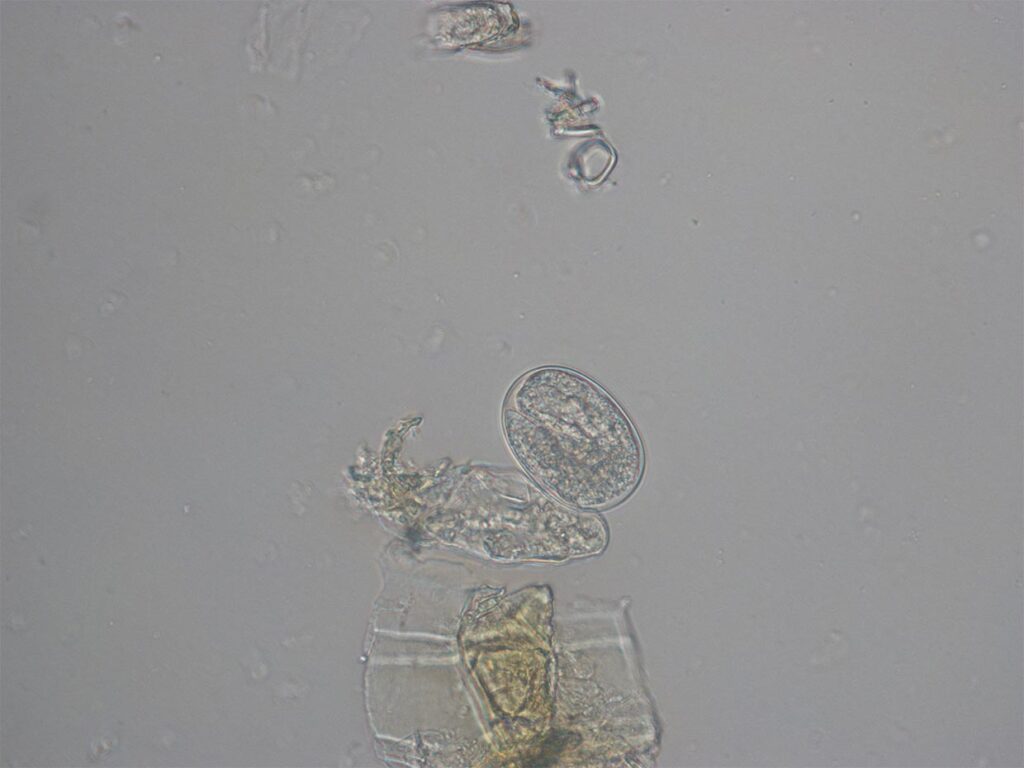

Being zoonotic agents, the dog roundworm (Toxocara canis, Toxascaris leonina) (Figure 1) and, more rarely, the raccoon roundworm (Baylisascaris procyonis) can also infect humans. If humans, especially children, ingest the infectious eggs, the larvae (larva migrans) may migrate through various tissues and organs after hatching, similar to the situation in dogs. This may cause visceral toxocariasis (VT) or visceral larva migrans (VLM), with a reduced general condition, fever, cough, apathy, weight loss, nephritis, myocarditis, and in rare, serious cases with CNS involvement (neurotoxocariasis). Risk factors of zoonosis in humans include juvenility and especially contaminated public sandboxes or contaminated food, as well as low awareness of hygiene.

The hookworm Ancylostoma caninum is distributed worldwide; dogs and cats, especially puppies and kittens, are considered the definitive host and reservoir.

Larvae hatch from eggs released into a moist environment and develop into the infective stages within 2 – 4 weeks. Infection may occur by oral route through coprophagy or the ingestion of infected prey as well as by percutaneous route, but galactogenic infection of the puppies is also possible. The larvae migrate via the bronchi, trachea, oesophagus and stomach into the jejunum and attach to the mucosa. They feed on blood and thus cause eosinophilic enteritis in the host, resulting in mucous to bloody diarrhoea. A massive infestation causes anaemia and in particularly severe cases infection can be fatal.

Human infection can also happen by oral route through smear infection or ingestion of contaminated food. The symptoms of the disease in humans are similar to those in dogs and are caused by the migrating larvae. There may also be percutaneous infections as a result of walking barefoot on contaminated ground, such as sandboxes or sunbathing lawns at swimming lakes. After percutaneous infection, a subcutaneous migrating larva, larva migrans cutanea, can be seen. It causes pruritus, erythema and inflammation of the skin. Feet and legs are particularly affected and the symptoms can last for 5 – 6 weeks. Cutaneous larva migrans is usually a self-limiting infection.

The threadworm Strongyloides stercoralis is found worldwide, the reservoir and definitive host are foxes, dogs and cats, especially puppies and kittens. Similar to hookworms, the filariform third-stage larvae penetrate the skin of the host, but they can also be ingested orally.

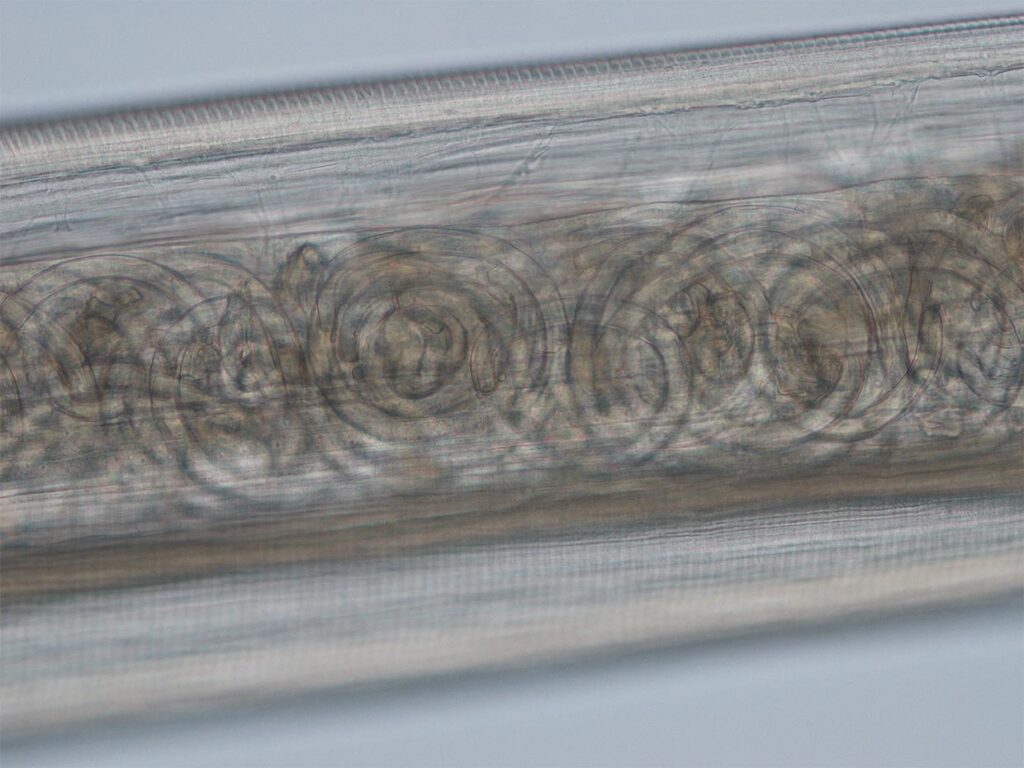

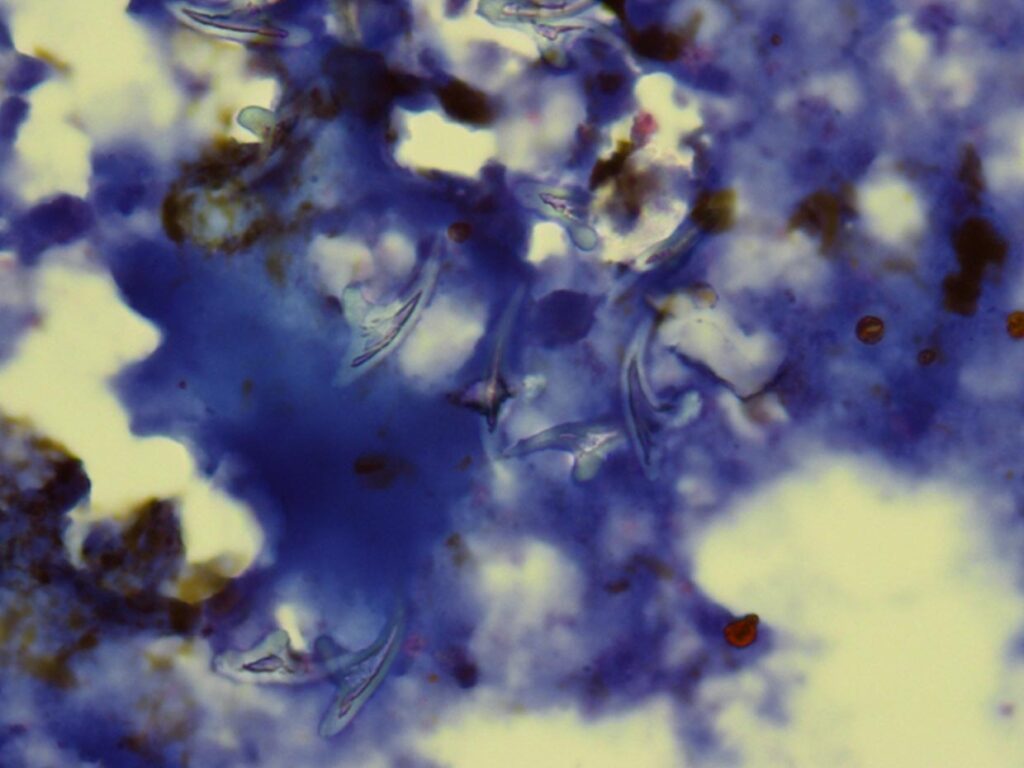

In the jejunum, adult worms can often persist clinically unnoticed for years and produce thin-shelled eggs. First-stage larvae already hatch during the intestinal passage; in a homogeneous cycle they develop into the infectious third-stage larvae within 24 hours if the environmental conditions are favourable. In a heterogeneous cycle, both male and female larvae can develop from first-stage larvae. This development cycle lasts several days, but leads to a massive multiplication of larvae in the environment (Figures 2 and 3).

-

Fig. 1: Toxascaris leonina: egg

Photo credits: Laboklin

-

Fig. 2: Strongyloides stercoralis: egg with larva

Photo credits: Laboklin

-

Fig. 3: Strongyloides stercoralis: larva

Photo credits: Laboklin

-

Fig. 4: Thelazia callipaeda: mature

Photo credits: Laboklin

-

Fig. 5: Taenia egg

Photo credits: Laboklin

-

Fig. 6: Liver puncture with Echinococcus hooks

Photo credits: Laboklin

Vector-borne nematodes with zoonotic potential

Different mosquito species (Aedes vexans, Aedes cinereus, Aedes sticticus, Aedes albopictus and Culex pipiens) act as vectors for Dirofilaria repens and Dirofilaria immitis and are competent intermediate hosts. As these vectors have very low host specificity, not only dogs and cats but also other mammals and humans can be infected with filariae.

The dog as the definitive host is infected when mosquitoes transmit third-stage larvae of Dirofilaria repens during the blood meal. The third-stage larvae undergo two more moults in the dog to reach the adult stage. The adult worms mainly parasitise in the subcutaneous tissue, especially in the head area, but they have also been found in the scrotum. Filariae are said to have a lifespan of up to 7 years. Throughout their life, the worms that reside in the subcutaneous tissue are able to produce microfilariae. These are ingested during the blood meal and the further development into infective third-stage larvae takes place in the mosquito. The third-stage larvae migrate to the mosquito’s proboscis to infect another definitive host.

In the human dead-end host, Dirofilaria repens can cause filariasis. After the bite, the larvae enter the bloodstream and reach various organ systems, including the skin, eyes or various internal organs, where they cause organ-specific symptoms. However, in humans, the parasite does not usually develop into the adult stage.

In addition to the adult worm, often an incidental finding, microfilariae in the peripheral blood can be detected by microscopy of a blood smear or by PCR from EDTA whole blood. Because of the long patency of subcutaneous adult worms, treatment must be continued for 6 months even after surgical removal. In addition, repellents should be used to ward off mosquitoes.

Dirofilaria immitis is endemic in most tropical and subtropical areas of the world and is becoming increasingly common in adjacent temperate regions. In Europe, the parasite is mostly found in the entire Mediterranean area, but has started to spread to the north. The infestation rate highly depends on the regional climate and the density of vectors, so that in northern Italy the prevalence in dogs is up to 80%. Even though the cases observed north of the Alps are most likely to be imported diseases, the relevant vectors can be found there.

The thread-like nematode is about 1 mm thick and reaches a length of up to 18 cm in males and 30 cm in females. Dirofilaria immitis parasitises in the pulmonary artery and the right heart of canids, occasionally also in felids. The density of microfilariae in the peripheral blood varies greatly during the day, reflecting the flight activity of the vectors. At times that are favourable for mosquitoes, the microfilariae accumulate in the capillaries of the parenchyma, predominantly in the lungs. It is assumed that this periodicity is primarily controlled by changes in the partial pressure of oxygen in the blood that take place during the course of the day After ingestion, the microfilariae continue to develop within the mosquito into infective third-stage larvae. This development varies with temperature; there is no development below 14 °C, if temperatures are around 18 °C, a third-stage larva develops within 29 days, at 20 °C it only takes 8 days. After being transmitted with the next blood meal, they moult into fourth-stage larvae in the subcutaneous connective tissue within 1 – 2 weeks p. i., then migrate to the muscle fibres and, after the last moult, enter larger veins as pre-adult worms. Approximately 70 – 100 days after the mosquito bite, the worm grows to a length of 2 – 3 cm and then reaches the pulmonary artery and the right heart. After a minimum of 180 days p. i. (but usually later), the parasites reach sexual maturity. Although adult parasites can persist for several years, the density of microfilariae decreases to levels below the detection limit in about 30 – 50% of dogs due to immune reactions.

Clinical signs develop gradually, with cough, dyspnoea and general weakness up to circulatory collapse. Signs and symptoms are initially caused by the mechanical obstruction of the blood flow. Worm metabolites can cause inflammatory reactions in the blood vessels which lead to thickening of the vessel walls. The resulting high blood pressure then puts a strain on the heart. There may be stasis-induced ascites and oedema. If adult worms enter the vena cava, they may cause obturation stenosis resulting in shock and death.

For diagnostic purposes, ultrasound scans, antigen detection of a “birth protein”, which is released into the peripheral blood during the birth of the microfilariae, as well as the detection of microfilariae in the peripheral blood by blood smear examination or PCR are available. For all diagnostic measures, the long prepatent period of 6 months must be taken into account when treating imported dogs or after spending holidays in endemic areas.

In humans, who are dead-end hosts, the mature stages of Dirofilaria immitis primarily lodge in the lungs, where they cause nodules of approximately 1 – 4 cm in size that can be detected by radiography. Infections are mostly asymptomatic, occasionally causing non-specific symptoms such as cough and subfebrile increases in temperature. In southern Italy, positive correlations of the prevalence in dogs and the disease in humans have been found.

In addition to repellents to ward off mosquitoes, larvicidal macrocyclic lactones can be used for prevention. If the disease manifests itself, treatment is often complex and difficult for the dog, as the sudden death of many macrofilariae can lead to obstruction of the pulmonary arteries and an excessive immune response to the foreign protein can cause the animal to have an allergic shock. As a result, various treatment protocols have been established.

Thelazia callipaeda, the oriental eyeworm of the order Spirurida, colonises the ocular orbit, the conjunctiva and the lacrimal duct, particularly of wild carnivores (Figure 4). Foxes are considered to be the reservoir, but also dogs, less often cats, and, especially in endemic areas, it may also infest humans.

Their range extends over southern Europe. If the parasites are detected in Germany, they are usually identified as “holiday souvenirs”, for example from Lake Maggiore or Lake Garda. The number of reports of autochthonous cases is increasing, which may be due to the spread of the vector as a result of climate change.

Males of the fruit fly species Phortica variegata act as vectors. They ingest the first-stage larvae of the viviparous eyeworms with the lacrimal fluid; depending on the temperature, the development into third-stage larvae in the vector takes 2 – 3 weeks. Transmission to the next definitive host then takes place when the fly feeds again on lacrimal fluid. There, the larvae develop into sexually mature adults within 2 – 6 weeks. They can persist for up to one year.

A mild infestation is completely asymptomatic, but Thelazia callipaeda can cause typical signs of conjunctivitis with increased lacrimation, ocular itching, swelling, keratitis, follicular hypertrophy and photosensitivity. Especially if conjunctivitis is recurrent, it is recommended to look for the small 0.5 – 2 cm long, whitish transparent worms. In addition to visual inspection, it is also possible to detect them after lavage of the nasolacrimal duct.

There is an increasing number of cases of human thelaziasis in southern Europe; according to the literature, mainly elderly people and children are infected. Affected people show signs of conjunctivitis with increased lacrimation and foreign body sensation.They also describe winding filaments in their vision. In humans, too, allergic conjunctivitis is often treated first, and detection and mechanical removal is then carried out only if the first attempts at treatment have failed.

Infection with Onchocerca lupi, which occurs world-wide but has been described as rare, has now also been detected in Germany. Various black flies of the genus Simulium act as vectors; the third-stage larvae are inoculated during the blood meal, and adult nematodes then develop in the subcutaneous connective tissue. Inflammatory reactions lead to the formation of granulomas, especially in the head area, conjunctiva and sclerae. Periorbital swelling occurs. Conjunctivitis, epiphora and corneal ulcers may develop. First-stage larvae migrate into the blood and the lymphatic system. During the next blood meal, they are ingested by the vector in which they develop into the infectious third-stage larvae. Onchocerca lupi is considered a rare zoonotic pathogen; in individual cases, it was able to infect humans in unusual sites such as in the eye or the vertebral canal.

Cestodes

The fox is considered the definitive host of the small fox tapeworm Echinococcus multilocularis of the family Taeniidae, but raccoons and raccoon dogs, which are becoming more common in Germany, are also highly susceptible definitive hosts. Obligate intermediate hosts are small rodents and other small wild mammals. Our dogs are also susceptible definitive and intermediate hosts. Infected dogs are usually asymptomatic even with very high worm burdens

The taenia eggs excreted in the faeces (Figure 5) have a high tenacity against environmental influences; they are further spread into the environment by shoes, tyres and water run-off.

Humans get infected through smear infections, drinking water, unwashed food, soil or close contact with a dog that excretes eggs. In human dead-end hosts, the infection leads to alveolar echinococcosis, with tumour-like lesions mainly located in the liver (Figure 6).

10 – 15 deaths per year are registered in Germany.

Diagnosis in dogs has considerably been improved by using PCR for detection; microscopically, the eggs cannot be differentiated from other taeniid eggs. A strict deworming strategy for our dogs can significantly reduce the risk for humans.

Dipylidium caninum, the tapeworm of the family Dipylidiidae, is the most common type of tapeworm in Europe. The proglottids with the egg packets of the so-called cucumber tapeworm enter the fur of the host via the perianal region and spread from there. If there is a flea infestation at the same time, released eggs can be ingested by flea larvae as intermediate hosts. In them, they develop into the infective cysticercoids. After oral ingestion of the infected flea, the cysticercoids are released during digestion, and within a month, the adult tapeworm develops in the intestine of the definitive host.

Humans are dead-end hosts and rarely acquire infection by ingesting infected fleas; it is mostly children who are affected. Infestation in humans usually remains undetected; severe infestation can lead to abdominal pain, weight loss and diarrhoea, often associated with pruritus ani. Even in children, the infection is usually self-limiting without treatment

Dr. Anton Heusinger

Further reading

-

Krauss H, Weber A, Appel M, Enders B, v Graevenitz A, Isenberg HD, Schiefer HG, Slenczka W, Zahner. Zoonosen: Von Tier zu Mensch übertragbare Infektionskrankheiten. 3. Auflage. Köln: Deutscher Ärzte-Verlag; 2004. S. 441-2; S. 492-4.

-

Jacob J, Lorber B. Diseases Transmitted by Man’s Best Friend: The Dog. Microbiol Spectr. 2015 Aug;3(4). doi: 10.1128/microbiolspec.IOL5-0002-2015.

-

Klaus C, Daugschies A. Hunde und Katzen mobil in Europa – aus parasitologischer Sicht. Der Praktische Tierarzt 102, 2021, S. 236-247. doi.org/10.2376/0032-681X-2113.