Every sample examination begins with preanalytics, which includes patient preparation, sample collection, transport to the laboratory, and sample preparation for analysis. The significance of each individual step often becomes apparent only when the sample cannot be evaluated, or when the results are questionable. The following information outlines key considerations for small mammal samples (blood, faeces, urine).

Even the best analytics can only be as good as the sample material submitted!

Blood test

Blood sampling is now just as much a part of routine diagnostics for most small mammals as it is for dogs and cats. A complete blood count, including haematology and clinical chemistryparameters, is essential, especially for diseases

that cannot be diagnosed directly based on clinical examin ation and medical imaging. Endocrinological tests and direct or indirect pathogen detection are also possible.

Important Aspects to Consider During Preparation

Since most small mammals are prey animals, these species are highly susceptible to stress. Therefore, handling should be as stress-free and brief as possible. A small mammal should only be removed from the transport box once everything is prepared.

Blood reference values for small mammals are not ‘fasted values’ because fasting periods can cause a standstill in the gastrointestinal tract, especially in small herbivores. Withholding food for 2-4 hours before blood collection is therefore only beneficial in small carnivores. Treats, such as paste, should only be given to ferrets suspected of having insulinomas after blood collection, as they could otherwise distort the blood sugar levels.

Assuming a blood volume of 6-8% of body weight (60-80 ml/kg bw), a maximum of 6 ml of blood per kg bw can be taken from a weakened small mammal on a single occasion.

The puncture site depends on the animal species. Large, easily accessible veins are preferred (e.g., venae laterales in rabbits and ferrets, cephalic vein (lateral) in guinea pigs). Large-bore cannulas (20-21 G) with a smooth interior, with or without a cone, enable the quick, clot-free collection of larger quantities of blood. Clipping the puncture site is rarely necessary. It is usually sufficient to moisten the fine fur at the puncture site with alcohol and part the hairs over the vein.

-

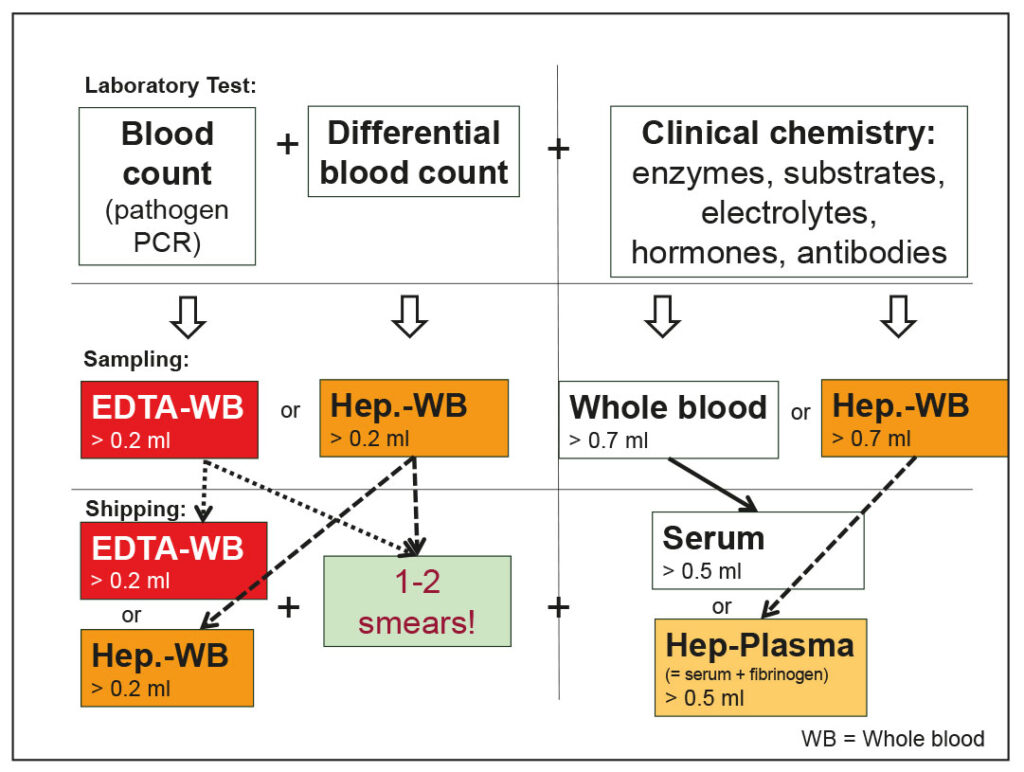

Fig. 1: Blood test – examination procedure, sampling methods, and shipping materials

Image source: J. Hein

-

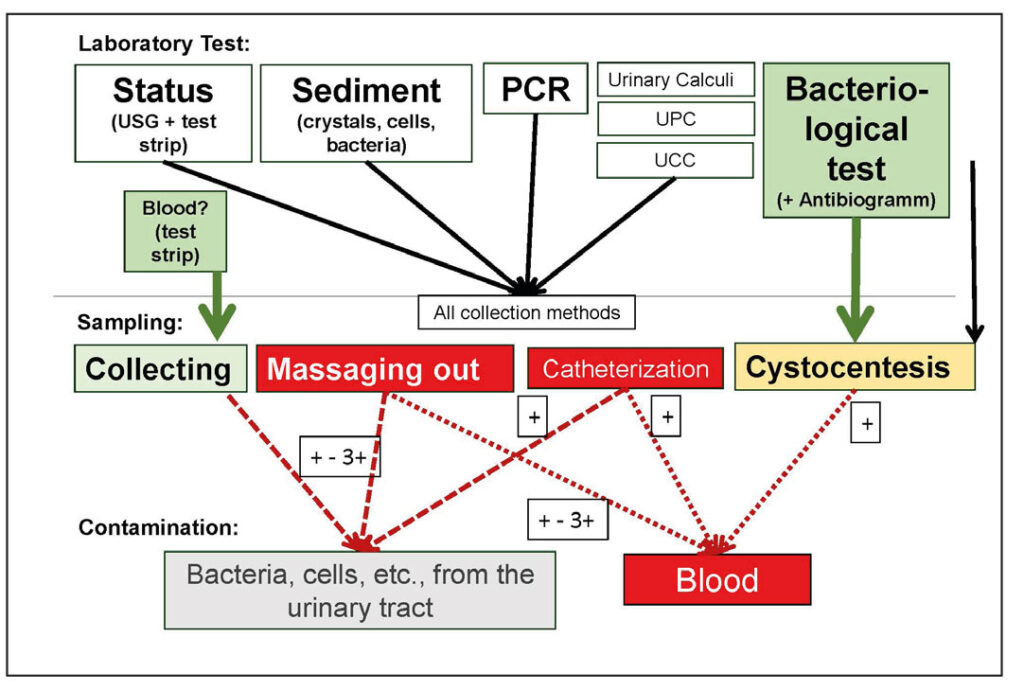

Fig. 2: Urine examination – examination methods, types of collection, and possible contamination (+ = severity of contamination)

Image source: J. Hein

-

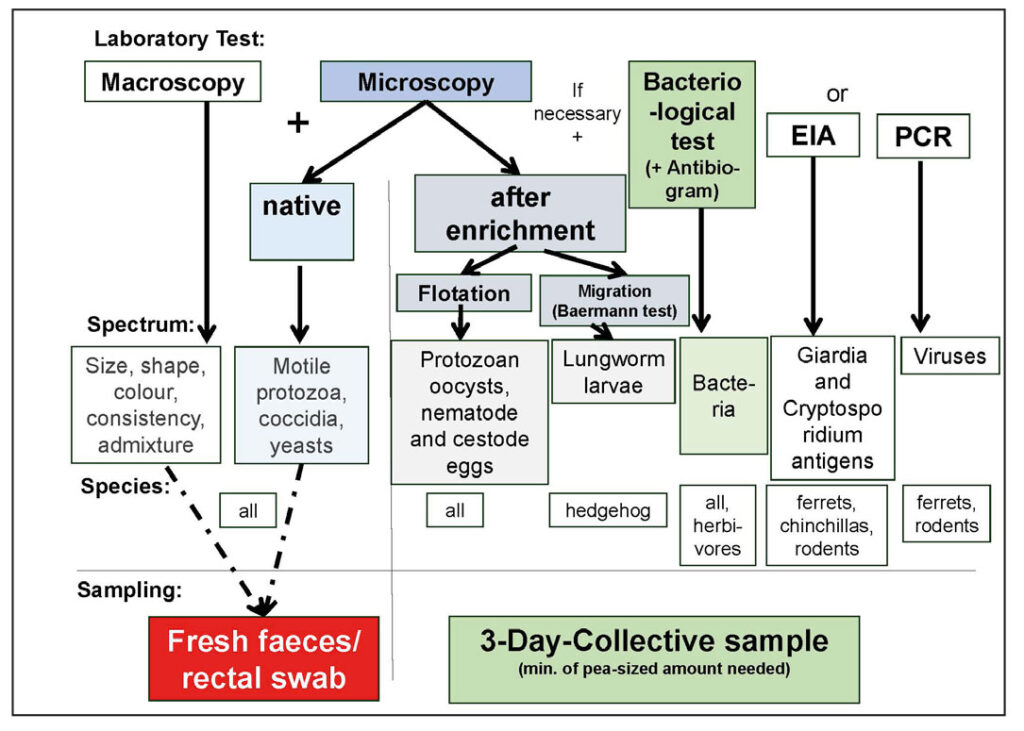

Fig. 3: Faecal examination – Examination methods, test spectrum, animal species, and collection methods

Image source: J. Hein

Required Sample Material

The sample material and quantity depend on the planned examination. Blood counts can be determined from EDTA blood (EB) and lithium heparin blood (HB), while clinical chemistry parameters can be determined from serum (S) or heparin plasma (HP).

In rabbits and ferrets, where larger blood sample volumes are expected, EDTA and whole blood tubes are usually used.

Beadless serum tubes facilitate pipetting. For smaller animals, the use of small EDTA and heparin tubes (1.3 ml) is preferred (1 EB + 1 HP or 2 HB (1 HB + 1 HP)) (Fig. 1).

Please always submit samples with smears!

If clots are present in a blood sample, the device cannot measure a blood count. However, if one or two blood smears prepared in the practice are included, at least a microscopic differential blood count can be performed.

No whole blood shipment for clinical-chemical parameters!

Whole blood for serum (with a standing time of 30-60 minutes) or heparinized blood (with no standing time) should always be centrifuged and pipetted for clinical chemistry analyses. Haemolysis can distort many parameters, leading to falsely elevated results (e.g., LDH, ALT, AST, PO4, K, fructosamine, etc.) or result in glucose metabolism by erythrocytes.

Special Considerations for Handling Small Mammals

The amount of blood that can be collected depends on the animal’s fixation, the choice of vein, and the size and position of the cannula in the vein. The larger the vein and cannula, the better the blood flow rate. This can be optimised by gently moving the cannula back and forth and/or slightly rotating it in the vein.

If clotting repeatedly occurs in the cannula, the type (internal bevel, size) of the cannula should be checked. The use of paediatric cannulas (21 G) without a cone, or breaking off the cone, can help increase blood flow. Coagulation in EDTA or Heparin samples can also result from the use of expired anticoagulants (always check the expiry date of the blood tubes) or insufficient mixing with the anticoagulant.

The tubes should be appropriately sized for the amount of blood collected (use small tubes) and should be gently rotated, then swung slowly (not shaken) when filling. Since most coagulation factors are in the first drops of blood, it is advisable to first collect whole blood for serum or plasma, and only then collect blood for the blood count (EDTA, heparin). The samples should be stored and shipped without exposure to heat or frost.

Key Parameters to Monitor in an Emergency

In an emergency and where small amounts of blood are involved, the most important parameters are those that indicate inflammation, bleeding, metabolic imbalances, and organ damage.

- Differential blood count: Small mammals generally have a lymphocytic blood count (exception: ferrets, which have a 50:50 ratio). An indication of inflammation (bacterial, neoplastic) is a so-called ‘pseudo-left shift’, a shift from a lymphocytic to a neutrophilic blood count without an increase in banded neutrophil granulocytes and without leukocytosis. Severe lymphocytosis and leukocytosis are occasionally observed in guinea pigs with leukaemic lymphoma. One drop of blood is usually sufficient for a smear.

- If bleeding is suspected, the haematocrit, total protein concentration, and possibly the erythrocyte and reticulocyte count (from EDTA or heparin blood) are of particular interest.

- To diagnose metabolic imbalances in blood, glucose and possibly triglyceride concentration determinations are helpful. Glucose measurement provides indications of hyperglycaemia (e.g., ileus in rabbits) or hypoglycaemia (e.g., insulinoma, sepsis). However, it is only meaningful if the determination is made from serum/plasma (or sodium fluoride blood) that has been properly and timely centrifuged. Measuring triglyceride concentration gives an indication of lipaemia. Blood gas measurement in small mammals is generally only performed in clinics with appropriate equipment.

- Markers for liver function include the enzymes GLDH (indicating acute hepatopathy), ALT, and/or AST (only in conjunction with CK, indicating severe and/or chronic hepatopathy). Markers for kidney function include creatinine (dependent on muscle mass) and urea (only diet-dependent in carnivores).

IIf the obtained of serum/heparin plasma is very small, it is advisable to make a note on the test order to prioritise the parameters.

Urinalysis

The classic urine examination (urine status, including urine specific gravity and test strips, as well as sediment analysis) is one of the simplest tests for small mammals and can usually be performed in-house. It provides important information not only on diseases of the urinary system but also on the metabolic status and possible endocrinopathies. Various pathogens can also be detected through bacteriological examination or PCR.

Important Aspects to Consider During Preparation

The preparation depends on the planned examination, which in turn is determined by the indication and the type of collection required (e.g., collection, massagging out, catheterisation, cystocentesis, Fig. 2). The required materials should be prepared in advance, and the manipulation should be as brief and stress-free as possible.

If uroliths or neoplasia are suspected, always rule them out by imaging (X-ray, sonography) before urine collection.

Required Sample Material

At least 0.5 ml of urine is required for the status and sediment analysis. The urine, which should be as fresh as possible, is analysed at room temperature. The indication is decisive for the type of collection, and this, in turn, affects the informative value of the urine examination.

- If blood in the urine is suspected, the urine must be passed freely and collected. Any type of bladder manipulation (e.g., massaging, catheterisation, or puncture) can cause minor bleeding, leading to false-positive blood detection, especially if crystals are present in the urine. In rabbits and guinea pigs, the amount of blood in the urine generally increases with repeated attempts at expression.

- Urine for bacteriological examination should always be obtained by cystocentesis, as all other collection methods may lead to contamination from the urinary tract or surrounding area. In rabbits and guinea pigs, the bladder can be easily grasped in the supine position, allowing for puncture without ultrasound guidance.

- For all other urine examinations, the collection method is of little importance.

Special Considerations for Handling Small Mammals

Porphyrins from food often lead to strong urine discolouration, which owners may easily misinterpret as blood. A test strip with a blood field provides clarity. However, it is often sufficient to draw up some of the urine into a syringe. If it is coloured, the urine in the dish will darken due to oxidation, whereas the urine in the syringe will not.

Centrifugation for sediment preparation is only useful with urine that is low in crystals and has a low urine specific gravity (USG). If the urine is rich in crystals, it should be added pure to the slide and capped. A drop of methylene blue under the cover slip facilitates the differentiation of bacteria (motile in fresh urine) and crystals.

Some infectious agents (e.g., Encephalitozoon cuniculi, European Brown Hare Virus, Leptospira, Rabbit Hemorrhagic Disease Virus, canine distemper virus) can be detected by PCR. Due to the intermittent excretion of pathogens, however, only a positive PCR result is always conclusive.

U-P/C and UCC are of limited value in small mammals (with the exception of ferrets). Urinary calculi analysis is rarely helpful in herbivores regarding therapy, as the stones mainly consist of non-dissolvable calcites (calcium carbonates and phosphates).

Key Parameters to Monitor in an Emergency

In small mammals, the urine status examination is particularly important in an emergency. The USG indicates dehydration or polyuria, while the urine pH and ketone body field (only acetone and acetoacetate) show whether a herbivore with a physiologically alkaline urine pH is still stable or is already slipping into acidosis. If the leucocyte and possibly nitrite field is positive, a drop of urine under the microscope quickly reveals whether bacteria are actually present in increased numbers.

Faecal examination

A faecal examination is typically carried out in the case of gastrointestinal symptoms and/or suspected endoparasites. However, it can also provide important information about feeding errors in small mammals.

Important Aspects to Consider During Preparation

Preparation is simple. Faecal samples are collected by the pet owner or by the examiner on-site (faecal tube) or rectally using a swab (direct smear).

Required Sample Material

A lentil-sized amount of faeces or a rectal swab is sufficient for the microscopic examination of fresh native samples on-site. Due to the intermittent excretion of parasites, the examination of a 3-day pooled sample is more informative.

Special Considerations for Handling Small Mammals

If “worms” are seen macroscopically in the faeces, these are usually Passau larvae. In the case of “intermittent diarrhoea” in rabbits, macroscopy (caecotrophs versus hard faeces) and microscopy (parasites, yeast, and fibre content) help assess the problem and evaluate the feeding.

Coccidia should always be treated, especially with new arrivals. Giardia is mainly found in chinchillas and ferrets but only need to be treated if causing symptoms. A bacteriological examination is useful in omnivores and carnivores if the parasitological examination is negative. In herbivores with predominantly bacterial fermentation, it is less useful, except in the search for human pathogens (e.g., Salmonella).

Key Parameters to Monitor in an Emergency

In an emergency, e.g., with a severely tympanic animal, a native smear of a small amount of faeces is often sufficient to detect motile protozoa, coccidia, or nematodes.

Conclusion

Laboratory diagnostics is not rocket science, even in small mammals! And if you are aware of the pre-analytical issues and avoid them, the results will be reliable.

Dr. Jutta Hein, Jana Liebscher

“Small mammals” submission form at Laboklin – one order for all available services!

- Individual determinations, screenings and species-specific blood profiles with hormones and serology

- Various urine tests and species-specific faecal profiles

- PCR, pathology, genetics, autovaccines, and more