Ear diseases in rabbits are a common reason for presentation in small mammal practice.

Unfortunately, they are also often incidental findings during clinical examinations. In most cases, otitis refers to inflammation of one or more structures of the ear and, as in dogs and cats, can be categorised as otitis externa, otitis media, or otitis interna.

Causes

Age, sex, or husbandry conditions have little influence on the development of otitis, although lop-eared rabbits are commonly affected. Due to anatomical restrictions caused by the drooping ears, stenosis of the external auditory canal can occur, leading to an accumulation of cerumen in front of the eardrum.

Restricted ventilation and increased moisture in the ear favour the development of otitis externa and possibly otitis media. Injuries, foreign bodies, ectoparasites, and ascending infections from the respiratory tract or teeth are further causes of otitis in rabbits.

Symptoms

Different symptoms may be observed depending on the underlying cause:

- Cerumen build-up in the outer ear: possibly reduced activity and responsiveness due to sound dampening.

- Otitis externa: head shaking, ear scratching, changes in the pinna (e.g. redness, warmth, discharge, swelling, bleeding), possibly aural diverticulosis (under the pinna), or a droopingear (in rabbits that normally have erect ears).

- Otitis media: may present with head tilt, facial nerve paresis or Horner’s syndrome

- Otitis interna: may include the abovementioned symptoms, as well as rolling, reduced general condition and decreased feed intake

Diagnostics

The ear examination includes a clinical examination, cytology, and, if necessary, bacteriological and mycological analyses of ear secretions (with antibiogram). If involvement of the middle or inner ear is suspected, additional imaging techniques such as X-rays or computed tomography are required. Other systemic infections are ruled out through blood tests, including differential blood count and antibody testing for Encephalitozoon cuniculi.

Further details on ear examination, cytology, and bacteriological analysis are provided below.

Clinical examination

The ear examination starts with a thorough inspection and palpation of the outer ear and surrounding area (checking for scratch marks, injuries, diverticula, or skin changes).

If the head is tilted, the eyelids and lips should always be examined carefully. Unilateral facial nerve palsy — indicated by contraction of the upper lip (Fig. 2), reduced eyelid closure, and/or Horner’s syndrome (miosis, ptosis, enophthalmos) — may suggest involvement of the middle or inner ear.

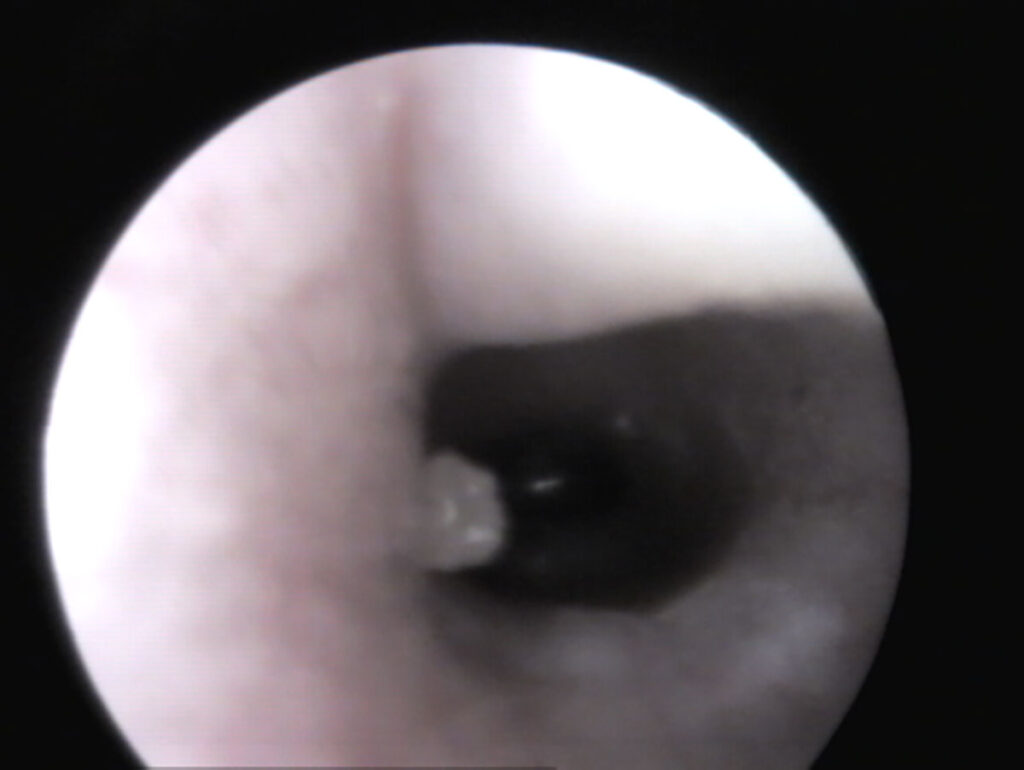

The external auditory canal is examined using an otoscope or video endoscope. In a healthy ear, gently pulling the pinna upwards (Fig. 1) usually allows visualisation up to the eardrum (Fig. 3). If material is present in the ear canal, it is important to determine whether it is merely accumulated cerumen (white deeper inside, yellowish nearer the opening) with no signs of irritation, or whether there are signs of inflammation such as redness, swelling, lesions, or liquefied secretions (Fig. 4). Potential primary causes like foreign bodies or ectoparasites should also be considered. Cytology helps in making this distinction.

Sampling

For proper sampling, an otoscope funnel, thin swabs (with transport medium), microscope slides, and cover glasses are required. Samples are usually taken from the external auditory canal in unsedated rabbits (middle ear samples are taken intra-operatively). Wrapping the animal in a towel (“wrapping”) helps to prevent defensive movements (Fig. 1).

To ensure the sample is taken as deeply as possible, the swab is carefully inserted through the otoscope funnel to just before the eardrum and gently rotated. It is then smeared onto one or two slides for cytology and subsequently placed in the appropriate transport medium tube for culture if needed. Swab samples can be stored at room temperature or refrigerated for up to 24 hours (shipment without refrigeration is possible).

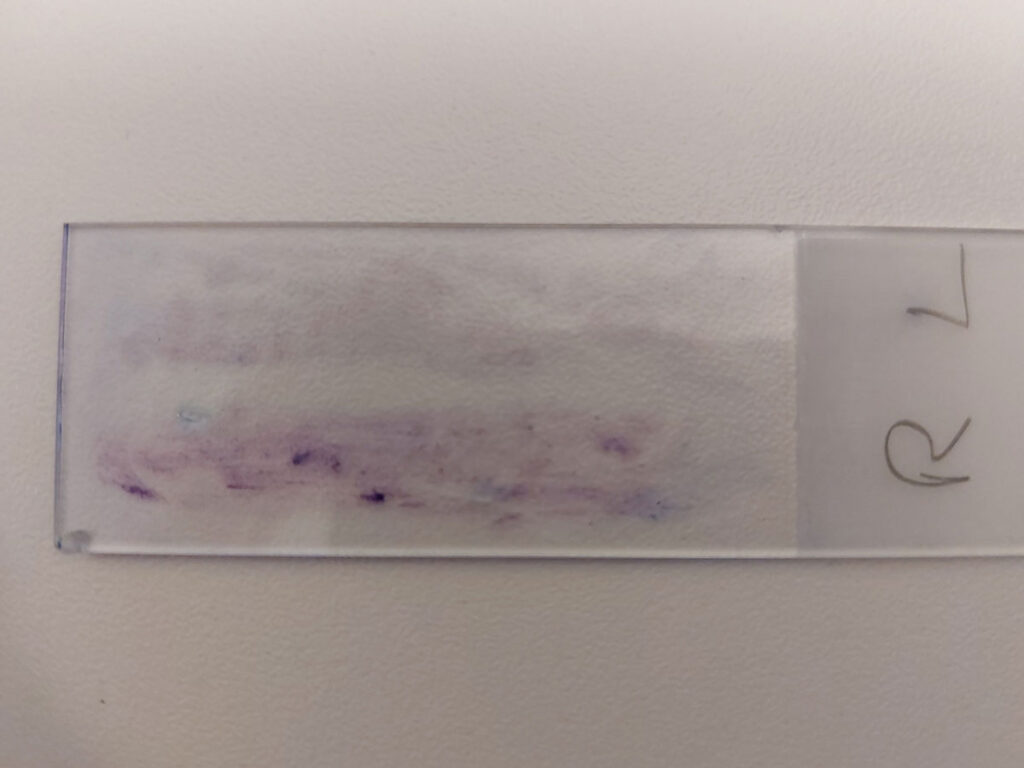

It is always recommended to sample both ears ‒ even, or especially, if only one ear is affected ‒ to gain insight into the patient’s normal ear microbiome (if needed, the samples can be spread side by side on the same slide) (Fig. 5)

Ear cytology

Cytology provides important information about the composition of the secretion (cerumen or pus) as well as potential primary causes such as ectoparasites, yeasts, and/or increased bacterial numbers. For cytological preparation, the swab is gently rolled out in a thin layer on two slides. After air-drying, one slide is analysed under the microscope (condenser down, aperture closed, magnification 100–400x) for ectoparasites. The second slide is stained – for example, with Diff-Quick® ‒ and after air-drying, is also examined (magnification 100–400x; 1000x with oil immersion, condenser up, diaphragm open)

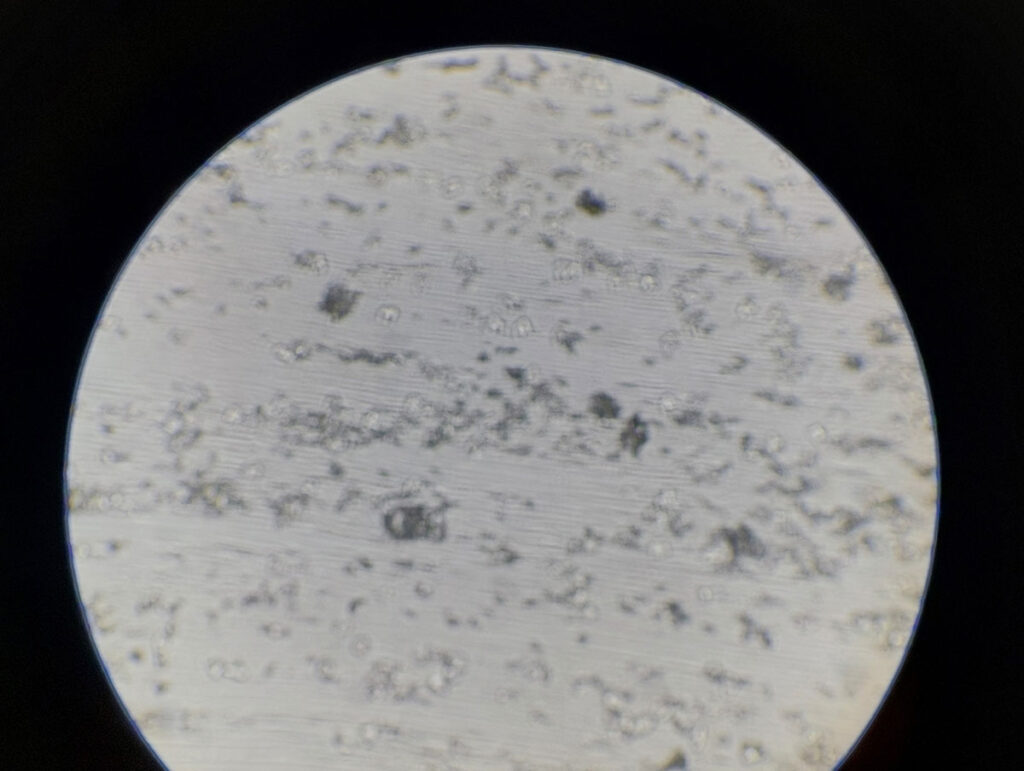

Cytology provides initial information about the type of secretion: uncoloured cerumen (Fig. 6) or clearly stained pus with DNA streaks (nuclear remnants of neutrophil granulocytes and keratinocytes), bacteria, or yeasts (Fig. 7).

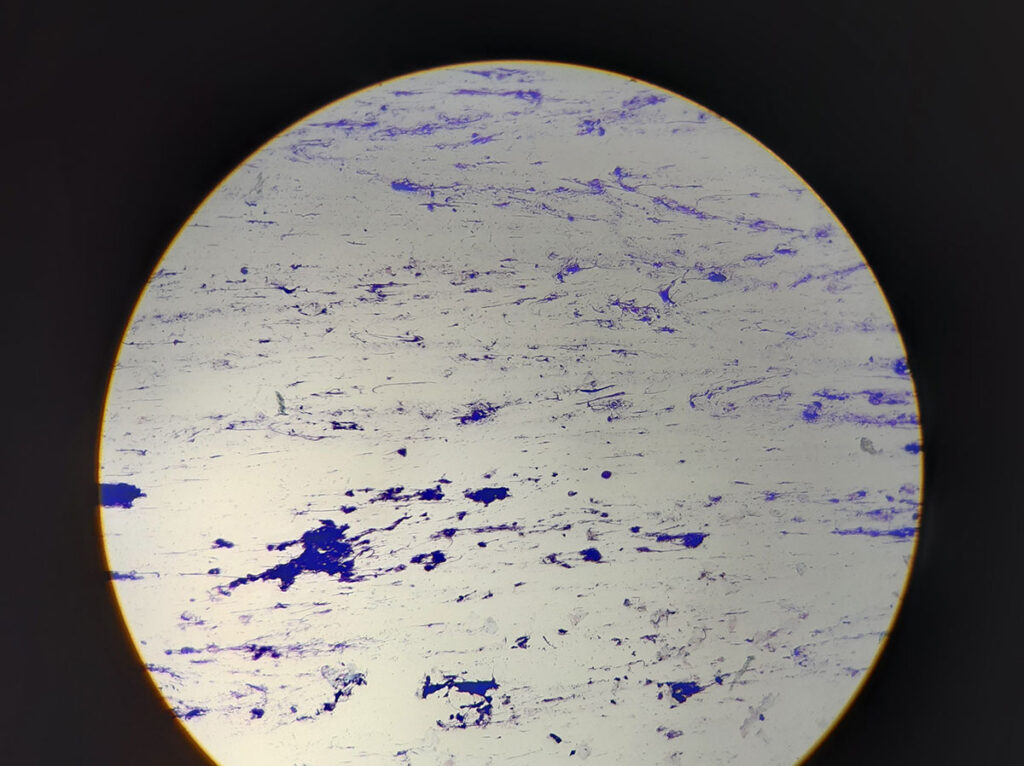

The amount of bacteria (cocci, rods) and yeasts (Malassezia) can also be assessed.

An increased number of DNA streaks and bacteria or Malassezia throughout the preparation indicates an inflammatory process. Bacteria (always the same size and shape) should not be mistaken for staining artefacts. Only a few intact neutrophil granulocytes are typically found in rabbit ear preparations.

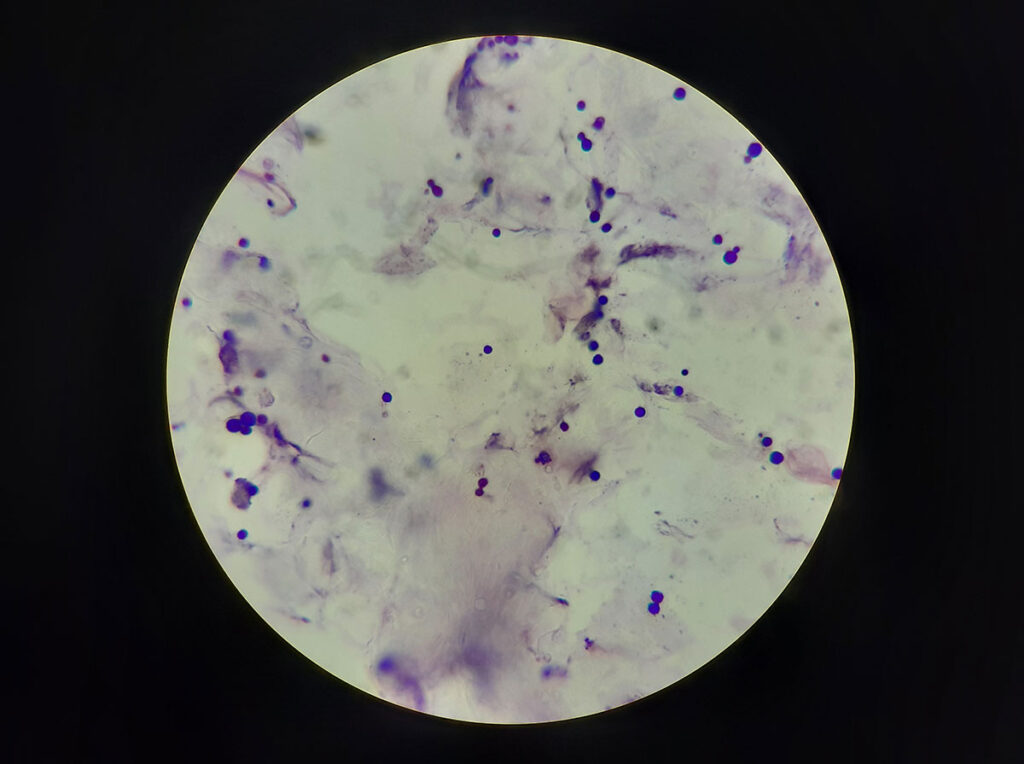

Malassezia (Malassezia cuniculi) appears round in rabbits, varies in size, may form buds, and stains deep blue (Fig. 8).

The cytological examination should be carried out prior to the initiation of therapy and repeated during follow-up. On the day of the check-up, no medication should be applied to the ear canal.

-

Fig. 1: Examination of the external auditory canal in rabbits using an otoscope

Image source: J. Hein

-

Fig. 2: Facial nerve palsy with right-sided contraction of the upper lip in a ram rabbit

Image source: J. Hein

-

Fig. 3: View of the eardrum of a rabbit (pars tensa – transparent, pars flaccida – woven)

Image source: J. Hein

-

Fig. 4: View into a rabbit’s outer ear filled with pus —

the otherwise non-irritated outer ear suggests that the pus originates from the middle ear

Image source: J. Hein

-

Fig. 5: Diff-Quick® stained slide showing smears from swabs of the right (R) and left (L) ears of a rabbit

Image source: J. Hein

-

Fig. 6: Microscopic image of cerumen in a rabbit’s ear. The cerumen barely absorbs any stain (magnification 100x, Diff-Quick®)

Image source: J. Hein

-

Fig. 7: Microscopic image of an ear swab from a rabbit with otitis externa, showing clearly stained DNA streaks, keratinocytes, occasional neutrophil granulocytes, and cocci (magnification 100x, Diff-Quick®)

Image source: J. Hein

-

Fig. 8: Microscopic image of an ear swab from a rabbit with yeast otitis, showing numerous deep blue, round Malassezia cuniculi. The cerumen barely absorbs any dye (magnification 100x, Diff-Quick®)

Image source: J. Hein

Cultural examination

For the bacteriological examination, swabs are plated on Columbia blood agar and Endo agar in the laboratory, then transferred to an enrichment broth. The plates are incubated aerobically at 36 ± 1 °C and checked for bacterial growth after 16–24 and 48 hours. Following 16–24 hours of incubation at 36 ± 1 °C, the enrichment broth is plated onto Columbia blood agar and Endo agar and incubated again under aerobic conditions for another 16–24 hours. Bacterial colonies that develop are identified or differentiated visually or by MALDI-TOF analysis.

For the mycological examination, swabs are also streaked onto fungal selective agar and incubated at 36 ± 1 °C for up to 7 days. Fungal growth is identified either macroscopically, microscopically, or via MALDI-TOF.

Ear microbiome

The middle ear is germ-free when intact. Even in a healthy state, the outer ear contains a small number of mixed flora, which are part of the physiological skin microbiome. These include Staphylococcus (S.) aureus, Streptococcus spp., Enterococcus spp., Bacillus spp., and individual Malassezia spp. (Reuschel 2018, Galuppi et al. 2020).

When environmental conditions change or disease develops, there is often an increase in Gramnegative pathogens and anaerobes.

In two recent German studies, up to 55 bacterial species from 12 families were isolated (Hein et al. 2021), with S. aureus (30%) being the most frequently detected, followed by Pseudomonas aeruginosa, Pasteurella multocida, Enterobacter cloacae, Escherichia coli, S. haemolyticus, Klebsiella oxytoca, and Pasteurella spp. (Reuschel 2018, Hein et al. 2021).

Up to 50% of ear bacteriological investigations yield negative results despite macroscopic evidence of disease, either due to superficial sampling of pus or prior treatment. Ideally, no medication — including ear cleaners or systemic antibiotics — should have been administered for at least 5 days prior to sampling.

To ensure successful cultivation and reliable results, the sample must be collected as deeply as possible and free from contamination, ideally before treatment begins.

Conclusion

Severe otitis can often be prevented through early detection and targeted treatment. Otoscopic examination and cytology are the initial diagnostic steps.

Dr Corinna Hader, Dr Jutta Hein

| Our services related to this topic | |

| #174

#204 |

Ectoparasites (microscopic)

Cytology |

| #150

#1061 #156 #725 |

Bacteriology (aerobic)

Bacteriology (aerobic + anaerobic) Bacteriology + Mycology + Antibiogram if necessary |

| #1175

#725 |

Bacteriology+ Mycology+ Ectoparasites (microscopic, cultural, bacteriological+ mycological)

+ Antibiogram |