The Importance of Drinking Water

Adequate water intake is essential to ensure high forage consumption. For this reason, water provision is a key aspect of feed management.

How can I ensure that animals drink enough? And how can I verify whether water intake is sufficient? Can data analysis help to monitor and optimise water consumption?

Drinking water analyses are primarily conducted on farms that use well water, usually on a regular basis as part of quality assurance. Similarly, when inconsistencies arise in the feed ration, the drinking water is often analysed, e.g. to determine how the supply of macro- and trace elements should be adjusted if the water is rich in certain elements.

It is also advisable to include drinking water analysis in investigations when disease incidence is high. What constitutes good-quality drinking water? What role do biofilms play in disease development?

Do Our Cows Drink Enough?

Dairy cows have a particularly high water requirement. Their bodies consist of up to 80 % water, and their daily requirement—depending on age, milk yield, ambient temperature, and feed intake—can reach up to 170 litres/day.

Appuhamy et al. (2016) describe the key factors determining the water requirements of dairy cows as follows:

- DMI – dry matter intake (kg/day)

- Milk – milk yield (kg/day)

- DM % – dry matter content of the ration (%)

- CP % – protein content of the ration (%)

- BW – body weight (kg)

- TMP – ambient temperature (°C)

- Na and K – concentrations of sodium and potassium in the ration

Water serves as a transport medium in the cow’s body and is essential for metabolism, thermoregulation, digestion, and immune function.

If water quality is poor, feed intake decreases significantly. Adequate water intake is also essential for milk production.

The factors influencing water intake are diverse.

Well-planned barn design with a sufficient number of appropriately sized and correctly positioned drinking troughs allows animals to meet their water requirements at all times. The The German Agricultural Society (DLG) recommends one drinking trough per 20 animals and a total trough length of 6 cm per animal. However, studies indicate that this may not always be sufficient. Increasing attention to this topic has highlighted the impact of improperly positioned troughs and herd hierarchy on reducing water intake (Burkhardt et al., 2025).

Environmental conditions such as ambient temperature, water temperature, and the physicochemical composition or contamination of water also affect its taste and, consequently, the volume of water consumed.

Laboratory parameters such as haematocrit and blood albumin can indicate insufficient water intake.

Modern technology also allows assessment of water consumption in cattle. For this purpose, microchips in the form of rumen boluses are used. Some boluses can measure internal body temperature in the rumen, enabling the detection of short-term temperature fluctuations during drinking. These fluctuations can be used to infer drinking behaviour (e.g., Smaxtec).

-

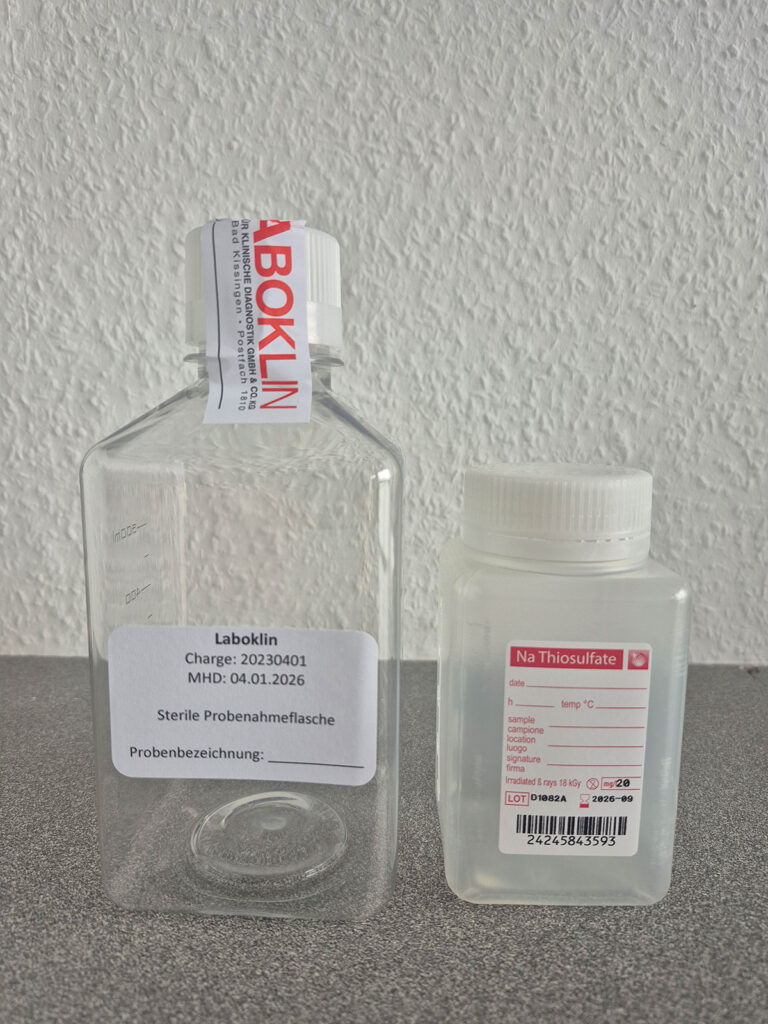

Fig. 1: Sample collection containers (available on request from Laboklin)

Image source: Laboklin

-

Fig. 2: Sampling from a hose

Image source: Laboklin

-

Fig. 3: Sampling from a drinking trough

Image source: Laboklin

What Is the Quality of Drinking Water?

Legal Considerations

From a legal perspective, drinking water is classified as an animal feed (Regulation EC No. 178/2002) and is subject to the Feed Hygiene Regulation (Regulation EC No. 183/2005). Drinking water must be suitable for the species in question and the drinking systems must be freely accessible. They should be designed to minimise the risk of contamination. Regular cleaning and maintenance of the systems is mandatory.

There are only recommendations from the BMLEH (Federal Ministry for Agriculture, Food and Home Affairs) regarding the quality of drinking water in livestock production. Unlike the Drinking Water Ordinance, these recommendations are not legally binding.

The Importance of Biofilms in Drinking Troughs and Water Lines

The quality of drinking water can be affected by the materials used and the formation of biofilms. Daily emptying of drinking troughs is not sufficient to ensure cleanliness. The most effective way to remove a biofilm is through drying or exposure to sunlight. In any case, regular mechanical cleaning with a brush should be performed.

Laboratory Diagnostic Analysis of Drinking Water

When is drinking water considered to be of good quality, and what do the individual parameters indicate? The following discussion addresses these points:

Criteria for Suitability as Drinking Water (BMLEH):

- Palatability is a fundamental prerequisite for adequate water intake.

- Safety/Compatibility ensures that all constituents are present only at concentrations that are not harmful to the animal.

- Usability ensures that no adverse effects occur on the watering equipment.

Correct Sampling

For microbiological testing, water samples should be collected under sterile conditions. A distinction is made between samples taken directly from drinking troughs and samples from inlet taps.

For general assessment of drinking water quality, it is advisable to take samples from an inlet tap or the source supplying the drinking system. In cases where herd problems are associated with insufficient water intake, additional samples should be collected directly from the animals’ drinking troughs and evaluated for suitability. The installed pipework can play a decisive role in water quality.

- Before sampling, the collection point should be sterilised by flaming the Alternatively, the tap can be immersed in an alcohol solution for several minutes.

- The clearly labelled sample container (Fig. 1) should be sterile; a mineral water bottle may also be suitable. It should be rinsed several times with the water to be sampled before use.

- Allow water to run for 2–3 minutes before taking the sample.

- Avoiding Contamination: unscrew the lid immediately before filling and close it immediately afterwards. Do not touch the interior of the container, and wear disposable gloves.

- Transport: keep refrigerated, protected from light, and transport as quickly as possible.

Sampling from a hose should be avoided, as effective chemical or thermal disinfection is not possible. Biofilms often develop inside hoses.

If sampling from a hose is unavoidable, it must be flushed thoroughly for an extended period to remove stagnant water with very high bacterial counts (Fig. 2).

Sampling directly from the animals’ drinking troughs is only appropriate in cases of acute symptoms (e.g., diarrhoea) when testing for specific pathogens (e.g., Salmonella) (Fig. 3). Such troughs often show elevated colony counts and contamination with, for example, enterococci or E. coli/coliform bacteria.

This type of sampling corresponds to purpose C in the drinking water sector (“as it is consumed”) and does not provide information on the suitability of the water supplied to the troughs as drinking water.

When taking samples for the analysis of chemical parameters, a sterile sampling container is not strictly required. However, water should be allowed to run for 2–3 minutes before sampling. During collection, care must be taken to prevent dirt or rust from entering the sample. Unlike microbiological sampling, the container should be filled completely without air bubbles and sent to the laboratory as soon as possible, preferably chilled.

Guidance Framework for the Feed Law Assessment of Drinking Water (BMLEH)

Microbiological Parameters

| Parameter | Orientation Value |

| Salmonella | 0/100 ml |

| Campylobacter | 0/100 ml |

| E. coli | 0/100 ml (ideally absent) |

| Heterotrophic plate count at 20 °C | < 10.000 CFU/ml |

| Heterotrophic plate count at 37 °C | < 1000 CFU/ml |

Recommended physico-chemical parameters

| Parameter | Unit | Guideline value | Notes | Drinking Water Ordinance |

| pH value | > 5, < 9 | may cause pipe corrosion and heavy metal release | 6,5 – 9,5 | |

| Electrical conductivity | µS/cm | < 3000 | Higher values may impair palatability and induce diarrhoea | 2790 |

| Total soluble salts | (g/l) | < 2,5 | Refers primarily to NaCl content | |

| Oxidisability | (mg/l) | < 15 | Indicates the presence of oxidisable substances / biofilm burden | 5 |

Recommended chemical quality parameters for drinking water

| Parameter | Recommendation (mg/L) | Possible disturbances | Drinking Water Ordinance (mg/L) |

| Ammonium (NH4+) | < 3 | Indicator of contamination | 0,5 |

| Arsenic (As) | < 0,05 | Health disorders, reduced performance | 0,01 |

| Lead (Pb) | < 0,1 | 0,01 | |

| Cadmium (Cd) | < 0,02 | 0,005 | |

| Calcium (Ca) | 500 | Functional disorders, lime deposits in pipes and valves | No limit value |

| Chloride (CI-) | < 250 (poultry) < 500 (others) |

Wet droppings | 250 |

| Iron (Fe) | < 3 | Antagonist to other trace elements, deposits in pipes, biofilm formation, taste alteration | 0,2 |

| Fluoride (F) | < 1,5 | Disturbances of teeth and bones | 1,5 |

| Potassium (K) | < 250 (poultry) < 500 (others) |

Wet droppings | No limit value |

| Copper (Cu) | < 2 | Total intake must be considered in sheep and calves | 2 |

| Manganese (Mn) | < 4 | Precipitations in the distribution system, possible biofilms | 0,05 |

| Sodium (Na) | < 250 (poultry) < 500 (others) |

Wet droppings | 200 |

| Nitrate (NO3-) | < 300 (cattle) < 200 (others) |

Risk of methaemoglobin formation, total intake must be considered | 50 |

| Nitrite (NO2-) | < 30 | Risk of methaemoglobin formation, total intake must be considered | 0,5 |

| Mercury (Hg) | < 0,003 | General disturbances | 0,001 |

| Sulphate (SO42-) | < 500 | Laxative effect | 250 |

| Zinc (Zn) | < 5 | Mucosal alterations | No limit value |

Conclusion

In addition to microbiological parameters, such as pathogenic E. coli or Salmonella, chemical parameters such as sulphate and nitrate in drinking water play a particularly important role in cattle health. Calves are generally more susceptible than adult animals. Sulphate concentrations of 500–600 mg/L in calves can negatively affect faecal consistency, while higher concentrations (> 2500 mg/L) may cause severe clinical symptoms resembling vitamin B1 deficiency, which can be explained by polioencephalomalacia (Kamphues et al., 2007).

These examples demonstrate that providing cattle with ad libitum access to suitable drinking water is crucial for maintaining health and performance. At Laboklin, we are happy to assist you in assessing the quality of your drinking water and to provide expert guidance on its interpretation.

Dr. Martin Felten, Dr. Anna-Linda Golob,

Swanhild Wagenfeld