Haemonchus contortus, commonly known as the red or twisted stomach worm, is a parasitic nematode belonging to the family Trichostrongylidae. It is one of the most significant gastrointestinal parasites of ruminants, particularly affecting sheep and goats. In recent years, it has also become increasingly prevalent in New World camelids, where it can likewise cause serious health issues. As a blood-feeding parasite, it can induce severe anaemia, which may lead to ruminal stasis and even death.

Due to its high pathogenicity, rapid development cycle, and growing resistance to anthelmintic treatments, Haemonchus contortus presents a major challenge in the management of both ruminants and New World camelids. In the original habitat of New World camelids – the high, arid regions of the Andes – Haemonchus contortus is only sporadically found. In contrast, the warmer and more humid climate of Central Europe offers more favourable conditions for the development and reproduction of the larvae. As a result, pasture-based husbandry systems, which are the most common form of keeping New World camelids in Germany, can lead to significant pasture contamination and infection pressure.

Morphology and Life Cycle

Adult worms measure approximately 10–16 mm in males and 20–30 mm in females. They parasitise the mucosa of the abomasum in ruminants or the third compartment of the stomach (C3) in New World camelids. Using a tooth-like structure in their buccal region, adult worms rupture small blood vessels in the gastric mucosa and feed on the host’s blood. The presence of blood in the worm’s intestine gives the females their characteristic red-and-white striped appearance, as the dark red intestine spirals around the paler uterus filled with thousands of eggs.

Each female can lay up to 5,000 eggs per day, which are excreted in the host’s faeces. Larval development is fastest under warm and moist conditions (20–25 °C): L1 larvae hatch within 1–2 days then moult into L2 and subsequently develop into infective L3 larvae within about one week. The L3 stage is highly resistant to environmental stressors and can survive lower temperatures. In moist environments, L3 larvae can actively ascend blades of grass and are ingested by the host during grazing. After ingestion, the larvae migrate to the crypts of the abomasal (or C3) mucosa, where they develop into L4 and then into adult worms. The cycle continues as these adults begin to produce eggs, which are again shed in faeces. The entire life cycle typically takes 3–5 weeks and can repeat several times per year.

Under warm and humid conditions, H. contortus populations in a herd or pasture can increase exponentially. The resilient L3 stage can survive mild winters on pasture, contributing to reinfection in spring. Additionally, within the host, L4 larvae or adult worms can enter a state of arrested development (hypobiosis). This occurs in autumn, and development resumes at the end of winter, leading to heavy pasture contamination early in the grazing season. This so-called «spring rise» in egg shedding is further exacerbated in females by the periparturient egg rise, a physiological phenomenon linked to weakened immunity during pregnancy, parturition, and lactation. As a result, pastures can become heavily contaminated within a short period, exposing young animals to high infection pressure from birth.

- Haemonchus contortus: Diagnosis, treatment and prevention in sheep, goats and New World camels

-

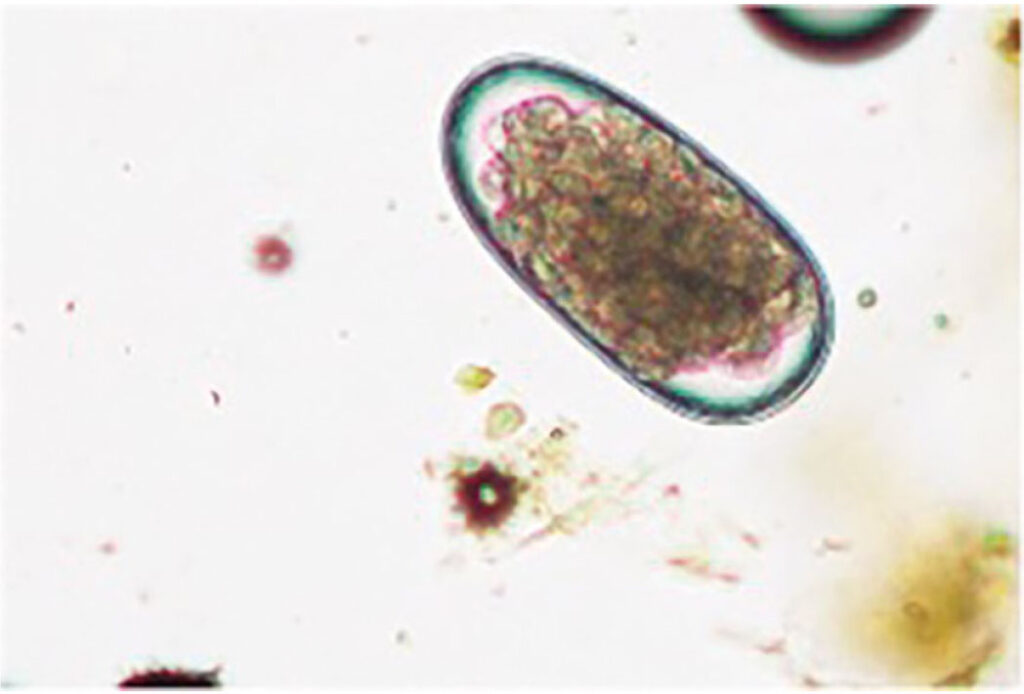

Abb. 2: Morphologie Trichostrongyliden- oder MDS-Ei: oval,glatt, 16 oder mehr Furchungszellen und ca. 70-98 x 30-50 μmgroß

Bildquelle: Laboklin

-

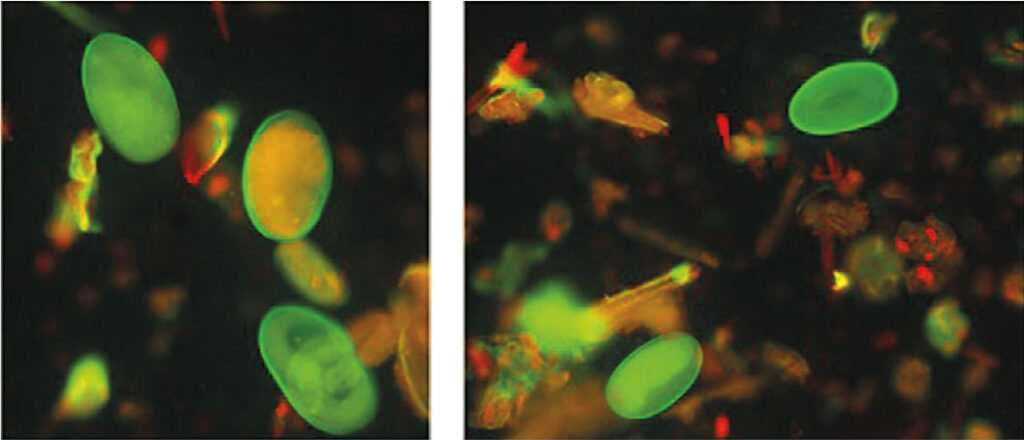

Abb. 3: Fluoreszenz von Haemonchus contortus-Eiern nach Erdnussagglutinin-Färbung

Bildquelle: Laboklin

Pathogenesis and Clinical Symptoms

Haemonchus contortus feeds on blood from the gastric mucosa in its adult stage. A single worm can cause an estimated daily blood loss of approximately 0.05 ml. Infections involving more than 5,000 worms may therefore lead to a loss of around 250 ml of blood per day. This results in anaemia, hypoalbuminaemia, and associated deficiencies in nutrients and minerals. Clinical signs can range from chronic to acute, and in some cases even to peracute progression.

Chronic infections are typically characterised by reduced performance and weight loss (emaciation). Gastrointestinal symptoms are not typical for this parasitosis, although diarrhoea may occur. Dark-coloured faeces may be observed as a result of occult blood leaking from lesions in the gastric mucosa. Oedema in the head and chest region – particularly the characteristic submandibular oedema, also known as «bottle jaw» – is a consequence of hypoalbuminaemia.

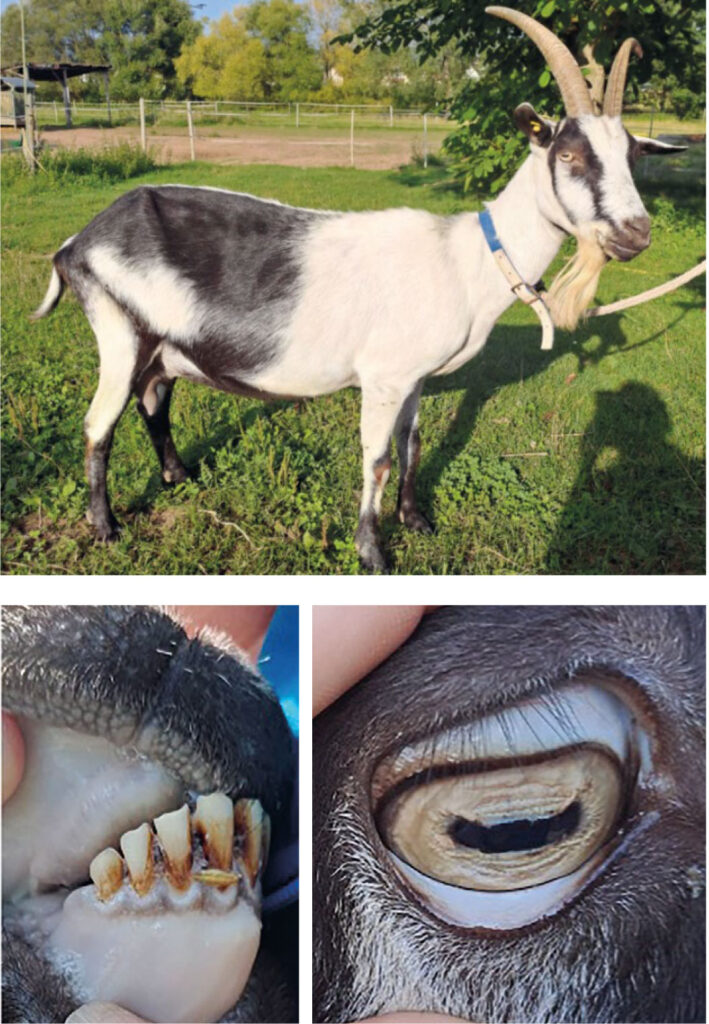

In cases of severe to massive Haemonchus contortus infestation, where the parasite can rapidly complete its reproductive cycles, acute massive anaemia may develop. This condition is characterised by porcelain-coloured mucous membranes (Fig. 1), tachycardia, tachypnoea, general weakness, and apathy – sometimes progressing to recumbency. Young animals are particularly vulnerable, as are pregnant females and nursing dams. Lambs, for example, can only mount an effective immune response against the parasite from around six months of age, leaving them susceptible to uncontrolled colonisation of the abomasum. Due to their lower body mass, the heavy blood loss affects young animals especially severely, often resulting in death within a few days.

Diagnostics

Clinical Examination

A clinical examination combined with anamnesis provides an initial indication of infection. The most important differential diagnosis for anaemia in small ruminants and New World camels is haemonchosis. Other potential causes to consider include haemotropic mycoplasma infection, ulcers of the abomasum or C3, other sources of bleeding, and chronic nutritional deficiencies.

Clinical diagnosis can be supported by blood tests or haematocrit measurements. Additionally, Body Condition Score (BCS) and FAMACHA© scoring are useful tools for monitoring infection severity and guiding treatment (see Treatment and Prophylaxis).

Coproscopy

For parasitological examination, faecal samples collected over three consecutive days are most suitable. The samples should be fresh and collected without prolonged contact with the ground to avoid contamination. Ideally, several faecal samples from successive defecations should be gathered.

In parasitological examination using flotation, eggs of Haemonchus contortus can be detected microscopically but cannot be morphologically distinguished from those of other gastrointestinal strongyles (MDS) (Fig. 2). A high concentration of MDS eggs may indicate a significant Haemonchus infection. Differentiation of species is possible through larval culture or fluorescent staining with peanut agglutinin. Although larval culture allows identification of MDS species, it is time-consuming and requires careful analysis.

Fluorescence staining takes advantage of the differing lectin-binding abilities of MDS eggs. Peanut agglutinin, coupled with a dye, binds to the egg surface of Haemonchus contortus and can then be visualised in colour under a fluorescence microscope (Fig. 3). This allows for clear differentiation from other MDS eggs, as the agglutinin does not bind to their surface.

Molecular Biological Methods

The polymerase chain reaction (PCR) detects specific DNA sequences of the parasite and allows for highly sensitive and specific identification of Haemonchus contortus. PCR does not detect intact structures, but rather DNA fragments.

As a result, a sample may still test positive even when no infectivity remains – for instance, following deworming. For this reason, PCR is not suitable for assessing the success of anthelmintic treatment. However, it can be used to analyse older samples that would no longer be fresh enough for reliable coproscopy.

Treatment and Prophylaxis

Worldwide, resistance to anthelmintics in gastro- intestinal nematodes is increasing at an alarming rate. Due to the high reproductive rate of Haemonchus contortus, large populations develop in which more spontaneous mutations occur, potentially leading to resistant worms. Because of the significant animal health and economic damage caused by Haemonchus contortus, the parasite is also under strong selection pressure from frequent treatments. Treatment failure due to resistance occurs across all active ingredient groups, and resistance to newer active substances has already been reported. Careful use of anthelmintics, combined with a well-planned deworming strategy and good pasture management, is essential.

For each herd, it is important to identify the anthelmintics that are most effective. This is achieved through egg count reduction tests (FECRT). Faecal samples are collected before deworming and 10–14 days afterwards, and worm burden is quantified using the McMaster method (eggs per gram of faeces = EpG). A treatment is considered successful if the egg count is reduced by at least 95%.

If deworming is unsuccessful, not only should the active ingredient be changed, but the entire active ingredient group should be switched. A follow-up success check using the McMaster count should then be performed.

To limit the further development of resistance, selective deworming should be practised. This means that only specifically identified animals receive treatment. This is important because, in treated animals, only resistant worms survive. If all animals were dewormed and then possibly moved to a new pasture, the fresh grazing area would become contaminated solely with eggs from resistant worms. This so-called ‘dose and move’ approach must therefore be abandoned. If some animals remain untreated within a herd, they continue to shed eggs from non-resistant worms. This helps dilute the population of resistant worms, allowing sensitive worms to keep passing on their sensitive genes to the overall population.

Which animals should be dewormed?

The selection of animals to be dewormed is based on faecal sample analysis. If there is a high-level infestation, treatment should be carried out.

A precise quantification is also possible here using the McMaster method. Different threshold values for eggs per gram (EpG) are defined for the various nematode species.

For infestation with Haemonchus contortus, deworming is recommended in sheep at counts greater than 200 EpG. For goats, llamas, and alpacas, the recommendation is above 100 EpG. Furthermore, deworming should be performed according to age groups. All young animals should be dewormed, as they are very susceptible and vulnerable. Adult females become increasingly resistant to gastrointestinal nematodes with age and can be assessed, for example, using clinical scores. Their need for treatment can be estimated based on weight development or body condition score (BCS). The mucous membranes of the eyes are also assessed, for example by using a FAMACHA© card. The so-called dag score (named after the English term for the dirty wool around the perianal area and hind legs in sheep) also provides indications of endoparasitosis. However, when looking specifically for Haemonchus contortus, the dag score should only be used in combination with the afore-mentioned assessment criteria, since diarrhoea is not a characteristic symptom of haemonchosis.

Correct dosing of anthelmintics is also crucial to avoid resistance development. Similar to antibiotic resistance, underdosing promotes the survival of partially resistant worms. Long-acting anthelmintics also encourage the selection of resistant worms, since among newly ingested L3 larvae only the resistant ones survive.

Good pasture management can help reduce infection pressure. Ideally, grazing and mowing of the pasture should alternate to reduce the larval burden. If possible, animals should not graze the pasture until it is completely short, as the larvae mainly reside close to the ground. Mixed or rotational grazing with other animal species can have a beneficial effect. These animals can ingest infectious larvae without becoming ill, thereby interrupting the reproduction cycle since they are not susceptible to species-specific parasites. Collecting faeces from the pasture can significantly reduce infection pressure. This is particularly feasible with New World camelids, as they tend to have designated dunging areas, enabling daily and thorough removal of Furthermore, it is advisable to observe a quarantine period for new arrivals in the herd. These animals should undergo quarantine treatment, including faecal examination with quantification and deworming if infested, followed by a success check using a Faecal Egg Count Reduction Test (FECRT)

Our services related to parasitoses

- Parasitological examination (flotation, SAFC) including differentiation of Haemonchus contortus

- Parasite profile(flotation, SAFC, modified McMaster method)

- Modified McMaster method(eggs per gram of faeces)

- Haemonchus contortus PCR

Dr. Britta Beck, Dr. Anna-Linda Golob,

Swanhild Wagenfeld